The Swamp Fox Revealed: Francis Marion-Related Objects in the Charleston Museum

By Carl P. Borick, Assistant Director

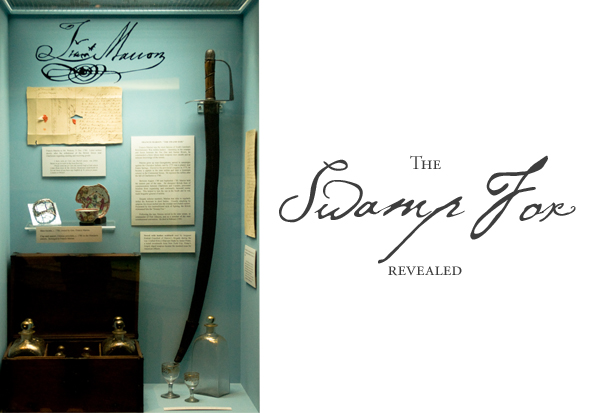

A close examination of artifacts in the permanent exhibitions at the Charleston Museum will reveal a number of references to Francis Marion, one of the most recognized names in South Carolina history. A dedicated case in the Revolutionary War section, for instance, contains an array of Marion materials. Did these objects belong to the legendary Swamp Fox and were they used by him or his men? Such an inquiry by a museum visitor is perfectly reasonable, especially when it comes to someone as enigmatic as Marion.

Francis Marion was born in 1732 at Goatfield Plantation, in present day Berkeley County, South Carolina. That is certain, but other events surrounding Marion are shrouded in mystery. Artists have composed many romantic images of him, but none are known to exist from his lifetime, so we do not even really know what he looked like. Unfortunately, much of what we have heard about Marion comes from the pens of men such as Mason Locke Weems, an ordained Anglican minister and author. “Parson” Weems was a well-meaning chronicler of early American heroes, including George Washington and Marion. He gave us the stories of Washington throwing the coin across the Potomac and chopping down the cherry tree. In creating the work about Marion, Weems greatly embellished a manuscript prepared by Peter Horry, one of his lieutenants. Horry commented to the parson after it was published “tis not my history but your romance.” Others such as William Dobein James and William Gilmore Simms supplemented the legend. Among their additions was the story of the British officer who visited Marion’s camp, and seeing that that his men lived only on sweet potatoes, vowed never to serve again against such brave men. Certainly a neat story, but probably untrue.

We do know that Marion was a highly-effective, partisan commander against British and loyalist forces in South Carolina. Despite impressive victories at Charleston in May 1780 and at Camden the following August, the British soon discovered that they could not control the interior of South Carolina, principally due to the efforts of leaders such as Marion, Thomas Sumter, William Harden, and Elijah Clarke. Marion, sometimes operating with just a few men or at other times with several hundred, harassed British supply lines or made surprise attacks on enemy troops. He was particularly successful against loyalist militia in the region between the Pedee and Santee Rivers. He was such a thorn in the side of the Crown in this area that General Cornwallis dispatched Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton on an expedition to destroy Marion. After pursuing him through swamps and dense woodlands for several days, Tarleton ultimately gave up the chase. Marion later cooperated with Continental forces under the command of General Nathanael Greene to retake posts such as Georgetown, Fort Motte and Fort Watson and commanded South Carolina state troops in the Battle of Eutaw Springs. After the war, he served in the South Carolina legislature, and despite his effectiveness against loyalists during the conflict, he was strongly in favor of leniency toward them after it.

Regarding artifacts related to Marion in the Museum’s collections, some examples were purported to have been carried by men who served with him. Two of these are swords. One is a late 18th century horseman’s saber typical of the kind carried by cavalrymen of the Revolution. Inscribed on the blade is the impressive motto “do not draw me without reason, do not sheath me without honor.” Scratched on the hilt of the sword is “Gen’l Marion, 1773”. The problem with this notation is that Marion was not promoted to general until 1780 and there was obviously no action taking place in South Carolina until after the war broke out in 1775. Although the owner of the sword may not have ridden with Marion, the piece is an excellent example of a period cavalry saber, and many like it were used during the war. It is on exhibit in the Museum’s armory.

Another sword is on exhibit in the Francis Marion case in the Revolutionary War exhibition. This was allegedly used by Sgt. Ezekiel Crawford while serving under Marion. The blade was fashioned from a whipsaw with a crude wooden hilt secured with iron straps. Whether Crawford carried it or not, this object is an exceptional example of patriots’ use of available materials to arm themselves during the American Revolution. Even more remarkably, the sword still has its original leather scabbard, very rare for an 18th century bladed weapon.

Other objects in the same case relate directly to Marion, including a shoe buckle, Chinese porcelain and a decanter case. Provenance on these items is primarily based on family tradition, so their ownership by Marion is uncertain. When he died, his estate went to his wife Mary and his adopted son. The shoe buckle and porcelain were seemingly not designed for wartime use. The buckle is made of silver with what appear to be precious stones interspersed along the face. These are actually “brilliants” – essentially glass, however. When in the field, Marion probably would have worn riding boots, which were much more practical than buckled shoes when on horseback, so chances are he did not use these during the war. One would expect it unlikely that a Revolutionary War soldier would carry the elegant china in the case while serving against the enemy. Marion may not have brought this with him but archaeological evidence from Fort Watson, which Marion and Light Horse Harry Lee captured from the British in April 1781, shows us that at least one British officer had moderately upscale tableware with him while campaigning in America.

The decanter case is essentially a traveling liquor cabinet, which an officer could use to transport spirits while in the field. Some 19th century sources claimed that Marion was “abstemious,” or that he was a very light drinker. Would a person who imbibed but little require such a facility for alcohol with spaces allocated for twelve bottles? The story about Marion being a “teetotaler” is probably fiction. In a letter he wrote to Benjamin Lincoln in March 1780 while he was guarding Ashley Ferry, he claimed that his men were “entirely out of rum.” Even if not a drinker himself, he certainly was in favor of the practice for his men. Moreover, a decanter case such as the Museum example would have been perfect for entertaining fellow officers while in camp. Circumstantial evidence is strong for ownership by Marion.

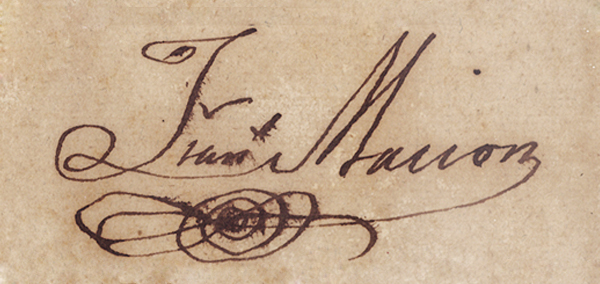

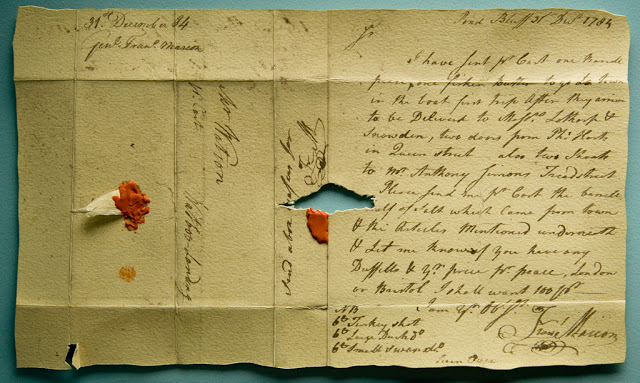

Two letter facsimiles in the case replicate originals in the Museum Archives. One was written to General Nathanael Greene on December 30, 1781. By this time in the war, the patriots had confined British forces to Charleston and its immediate environs. Marion informed Greene that he had posted large detachments of his men at Cainhoy and along the Wando River “to prevent small partys (sic) of the Enemy from ravaging the Country.” He also noted that he had found a way to sneak clothing out of British-held Charleston for his troops. The other letter, written after the war, concerns trade with several gentlemen who resided in the city. Both letters bear the unmistakable signature of Marion, and we can state unequivocally that the Swamp Fox held the originals in his hands.

The Heyward-Washington House, meanwhile, is currently home to a Windsor chair that Marion owned. This provenance is primarily based on family tradition, however. After his death, Marion’s widow supposedly gave the chair to the Schley family. It was kept in that family for nearly 150 years when Milby Burton, former director of the Museum, convinced descendants to donate it in 1957. Windsor chairs were common in the 18th century, and wealthy plantation owners would have had several, so Marion’s ownership of this piece is entirely possible. The card room in a gentleman’s home, where men drank, gambled, smoked and talked about issues of the day was a natural place for such chairs. Appropriately, you can see this example in the Heyward House card room. Possibly, Marion sat in this chair at his plantation house as he and Peter Horry recalled their exploits from the Revolutionary War. These discussions contributed to the Horry manuscript on which Parson Weems based his account of Marion. Little did the legendary Marion know he was unwittingly contributing to his own legend.

The Heyward-Washington House, meanwhile, is currently home to a Windsor chair that Marion owned. This provenance is primarily based on family tradition, however. After his death, Marion’s widow supposedly gave the chair to the Schley family. It was kept in that family for nearly 150 years when Milby Burton, former director of the Museum, convinced descendants to donate it in 1957. Windsor chairs were common in the 18th century, and wealthy plantation owners would have had several, so Marion’s ownership of this piece is entirely possible. The card room in a gentleman’s home, where men drank, gambled, smoked and talked about issues of the day was a natural place for such chairs. Appropriately, you can see this example in the Heyward House card room. Possibly, Marion sat in this chair at his plantation house as he and Peter Horry recalled their exploits from the Revolutionary War. These discussions contributed to the Horry manuscript on which Parson Weems based his account of Marion. Little did the legendary Marion know he was unwittingly contributing to his own legend.