The Mummified Egyptian Woman

The centerpiece of our Early Days exhibit is the mummified remains of a woman from Egypt, dating to the Late Period or Ptolemaic Period (ca. 700-300 BCE). Gabriel Manigault, the museum’s curator from 1873 to 1899 who wanted to acquaint Charlestonians with “any and everything illustrating the extinct civilizations of the world,” purchased this Egyptian mummified person from Horatio Wood in 1893.

Horatio Wood was American Vice-Consul to Egypt during the 1880s. He obtained the mummified woman from a Bedouin Sheik, who took the remains from a tomb near Cairo. The facial wrappings were soon removed, “to prove…that human remains were there.” The coffin, or sarcophagus now displayed with her, was acquired at the same time, but is of a later period, possibly Ptolemaic or Roman (332 BCE – 395 CE).

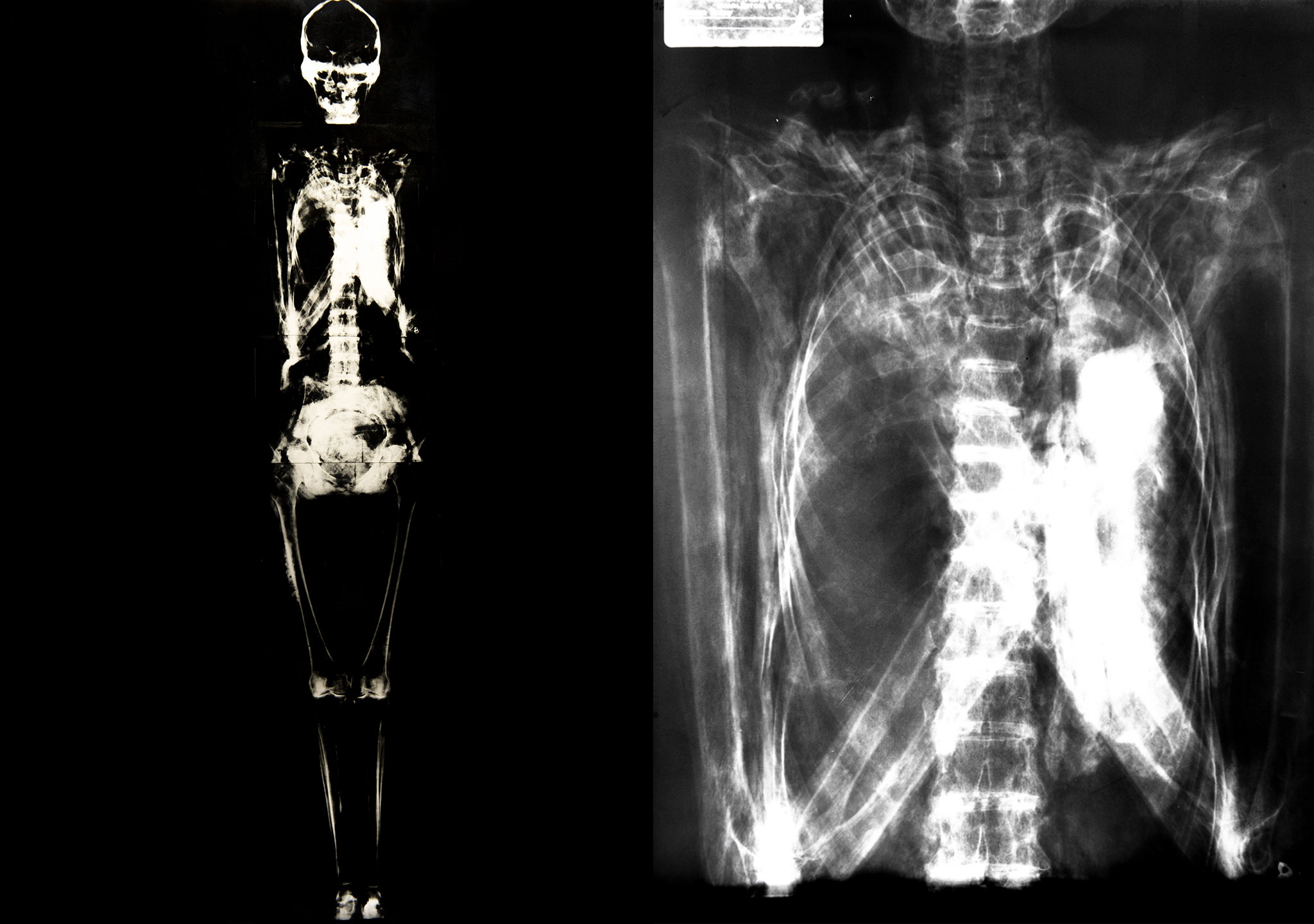

Over the years, we have learned the deceased woman was between 20 and 40 years old at the time of death. Her toes are individually wrapped and her arms are crossed. Her body is partially filled with resin, and the chest cavity contains a large double roll of material, possibly a book of prayers. X-rays taken in 1970 show fractures in the left sixth rib and the mid-shaft of the right clavicle. There is no evidence of healing, suggesting the bones were broken after death.

This unnamed mummified woman has been a cornerstone of the Museum’s exhibitions for the past 130 years. Ethics surrounding collection and exhibition practices have evolved during that time. The Museum purchased many of the international archaeological materials acquired in the late 19th century, or obtained them from private collections. Today, the movement and acquisition of such items is governed by the UNESCO Convention of 1970.

Mummified remains provide a view into ancient Egyptian funerary practices and beliefs. They also allow the viewer to have a personal connection with someone from an obscure bygone era. No longer referred to as “the mummy” we are striving to treat the mummified human remains with respect, reflected in language that addresses her humanity. Although her name was left behind in the tomb she was stolen from, we want our visitors to recognize her as a person who once lived.

-Martha Zierden

Curator of Historic Archaeology