Learning about the Enslaved at the Heyward-Washington House

87 Church Street has been home to many families, both free and enslaved. Today it is the location of the Heyward-Washington House. In 1772 construction was completed on a three story Georgian double house and 250 years later it is still there. This year we commemorate the history of the site including the house itself, the families that lived there, and the objects on exhibit. Join us for special exhibits, tours, and programs throughout 2022 as we mark 250 years since the Heyward-Washington House was built.

Though the Heyward-Washington House was completed in 1772, the site was home to enslaved people long before. John Milner, a gunsmith, inhabited the site in the 1730s. What we know about the enslaved during the Milner occupation was found through legal documents including his will. The Milner household included 11 enslaved workers, at least three of whom were skilled in the gunsmith business. In his will, Milner divided the enslaved among his children, and he instructed his heirs to sell two of the skilled tradesmen. One of the enslaved, Celia, was separated from her children as a result of the will. Celia was left to his daughter Martha, Celia’s son to Sarah, and Celia’s daughter to Mary. After Milner’s death, his son John Milner Jr. continued his father’s business on the site, including the enslaved workers.

To date, very little written documentation has been found regarding the enslaved that lived at the Heyward-Washington House under Thomas Heyward’s ownership. What we do know comes from analyzing the work yard of the site through archaeology and architecture. Work yards were the center of activity and the support system to any house in town, and included all outbuildings, wells, cisterns, drainage systems and gardens. Urban enslaved people would have spent most of their time here, preparing food, laundering clothes, and tending to the livestock and kitchen garden.

Everything about the architecture of the work yard shows the dominance of the main house. From the main house windows, one looks down onto the work yard, and no one can get in or out of the space without being seen. This dominance is also reflected in the large brick wall that surrounds the yard closing the space in. The main structure of the work yard is the kitchen-laundry-enslaved quarters. According to the late architectural historian Ed Chappell, it is the most informative pre Revolutionary kitchen-laundry-quarters surviving in Charleston. Other surviving examples from the period have been lost or converted to modern uses, making the Heyward-Washington House kitchen a particularly unique historic building in the city.

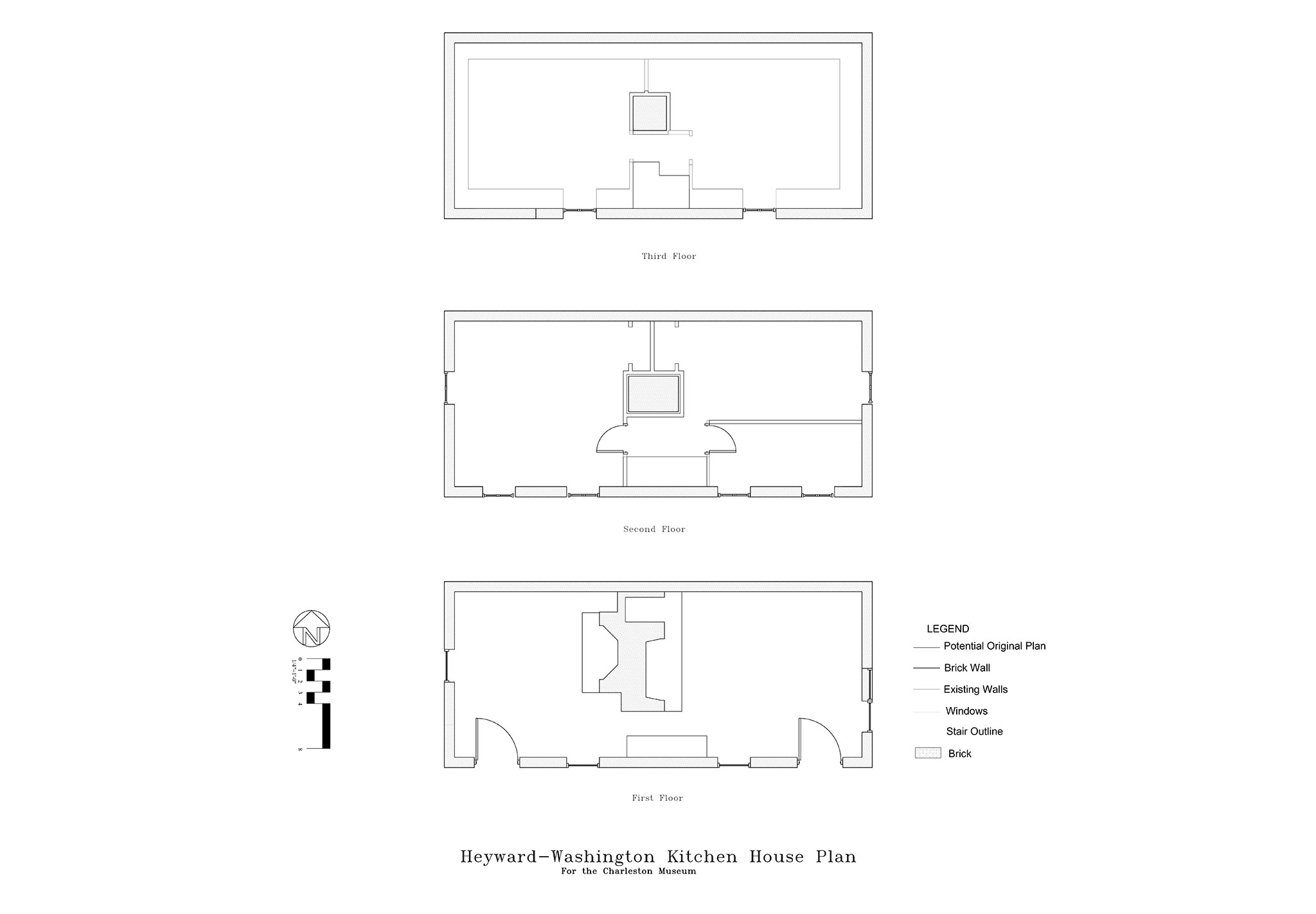

Scale drawings of the interior of the slave quarters show the various sizes of the rooms and suggest a hierarchy of the enslaved who lived there. The second and third floors are divided into 5 chambers. The second floor consists of one large room and two smaller rooms. The former had a sizeable fireplace with three windows; the other two had windows (two in the smallest and one in the other), but lacked direct access to the fireplace. To enter the rooms on the third floor, one had to duck under a shorter door frame to enter. Neither of these rooms had access to heat, and each is illuminated by only one window. According to the 1790 census, 17 enslaved people were present on the Heyward property. While a few may have slept in the main house, their living quarters would have primarily been divided among these five rooms.

In 1792, Thomas Heyward offered the house and property for sale, describing it as having “12 rooms with a fireplace in each, a cellar and loft; a kitchen for cooking and washing with a cellar below and five rooms for servants above; a carriage house and stables, all of brick surrounded by brick walls” (South Carolina Gazette, May 16, 1792).

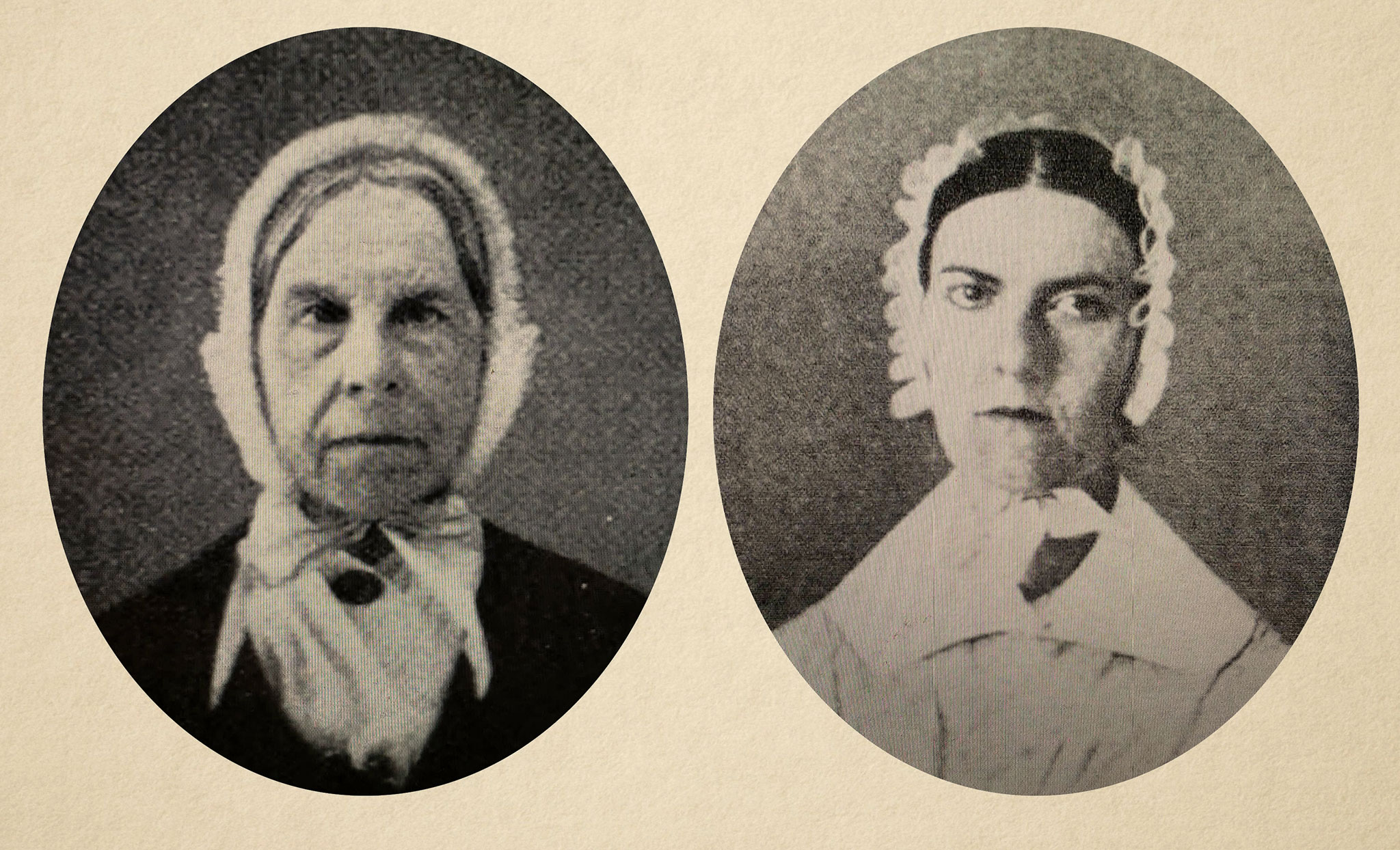

Sarah Grimké & Angelia Grimké Weld

January 1910, American Magazine. Article by Ida Tarbell. Vol. 69, no. 3

In 1794 the house was purchased by John Grimké, father of future abolitionists and women’s rights activists Sarah and Angelina Grimké. The writings of Sarah and Angelina provide more information about the enslaved of 87 Church Street from Sarah’s childhood recollections. Sarah was two years old when the Grimke’s first occupied the house, and they remained until she was about ten. Sarah recounts that around the age of five, after she saw an enslaved person being whipped, she tried to board a steamer to a place where there was no slavery. The incident which left such a strong impression on young Sarah likely took place in this work yard.

As a girl, Sarah was given Hetty, a young enslaved girl, to be her waiting maid. According to Sarah, they became close and she secretly taught Hetty to read and write. It was against South Carolina law to teach enslaved people to read and write, and when Sarah’s father discovered this they were both severely punished. Years later, she reflected on the incident, writing “I took an almost malicious satisfaction in teaching my little waiting maid at night, when she was supposed to be occupied in combing and brushing my locks. The light was put out, the keyhole screened, and flat on our stomachs before the fire, with the spelling book under our eyes, we defied the laws of South Carolina.”

It is through legal documents, archaeology, architecture, and primary written accounts that we continue to learn about the men, women, and children who were enslaved on the property at 87 Church Street. Theirs are stories that have not always been told, but without them the site – and the house – would not be what it is today.