Hand-drawn Map of James Island

PAST EXHIBIT

It is not often that archival items can be displayed. Due to their fragile nature (easily damaged by light, which is irreversible), it can be challenging to exhibit paper-based items. Luckily with the advent of social media – blogs, Tumblr, etc. – archival items are getting to “see the light of day” although not literally. While getting some of these pieces to social media sites can be problematic (we are still constrained by what can be scanned), it is extremely rewarding when we do as these objects provide some of the most fascinating, and sometimes personal, glimpses into the lives of our ancestors. For instance historical maps, a valuable and fascinating resource, offer us a chance to see our present world the way it used to be. While maps are inarguably an important means of studying the past and especially any given war, they are also valued for their beauty. Many of the early pieces were hand-colored and contain unique content making them collectible works of art. Maps produced in wartime are especially distinctive as troop positions and battle information were occasionally hand-drawn onto an existing map to create a truly precious item.

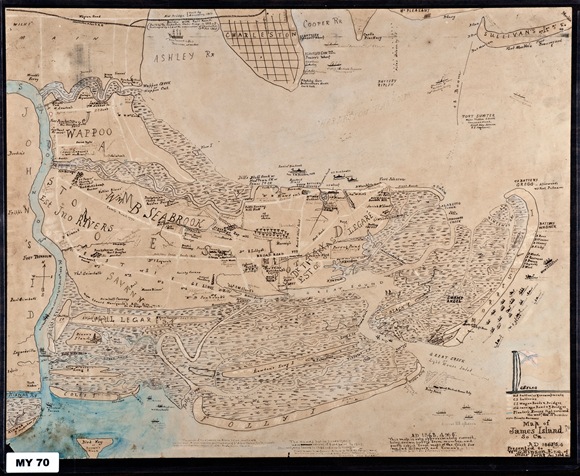

One of our favorite maps, featured here of course, is a hand-drawn map of James Island, signed R.E.M., circa 1887. R.E.M. is very likely Robert Eliott Mellichamp. While we are still conducting research, evidence indicates that Robert is the son of Reverend Stiles Mellichamp and Sarah Fowler Cromwell. Reverend Stiles Mellichamp was an Episcopalian pastor, possibly serving in the Civil War as a Chaplain. Robert was born in Beaufort in 1836 and the family moved to Charleston shortly thereafter. What is more certain is that during the war, he served in the Confederate Army, enlisting as a Sergeant in Buist’s Light Artillery (17th Regiment). The unit was split during a reorganization, becoming a company in the 18th Battalion, also known as the Siege Train, commanded by Major Edward Manigault. Robert’s rank at the end of the war was 2nd Lieutenant. Not only did Robert live his life in Charleston, with his extended family living on James Island, his Confederate service was in this area as well.

This is significant because the map depicts the positions of the Union and Confederate forces, both Army and Navy, as well as the blockade runners. The legend itemizes, by color code, Union batteries and encampments, Confederate batteries and Confederate wagon roads and bridges. Old carriage roads and bridges in addition to planters’ houses that survived the war are also noted; and, the map even details private avenues with ink dotted lines. The harbor entrance shows piles in a line from James Island connected to a Confederate Army boom from Sullivan’s Island with a break (possibly for the passage of blockade runners).

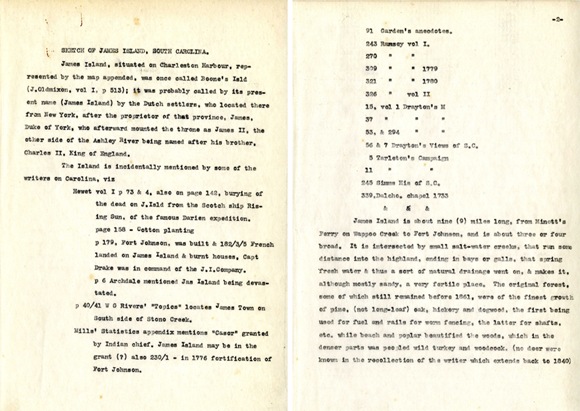

On the reverse of the map is a handwritten history titled Sketch of James Island. The sketch contains the history of James Island, from the author’s perspective, mentioning items of agricultural, historical and archaeological interest. Names of property owners, their seasonal work and movements are included. The sketch also details the author’s observations of life on James Island recounting the history of the local churches, perceptions of slavery and former enslaved people, habits of the property owners with notes on the conduct of their personal lives, the disappearance of public and private buildings and burial grounds of both whites and blacks.

This handwritten history was written by William Godber Hinson, another native of James Island, and the gentleman for whom the corresponding map was drawn. William was the son of Joseph Benjamin Hinson and Juliana Bee Rivers. He was the fourth of eight children, born in 1838. During the war, he served in the Confederate Army in the Rutledge Mounted Rifleman as a 2nd Lieutenant and was wounded three times in the line of duty. After the war, he returned to James Island. He inherited Stiles Point plantation from his uncle, William Godber, for whom he was named. He became a successful planter, a community leader and a well-read scholar.

The original Sketch of James Island is written in pencil, making it very difficult to read, and also quite light sensitive. The information, while roughly grouped into sections, is haphazardly placed so that the reader must turn the paper as not all the paragraphs are written cohesively. However, approximately a year later, in 1888, W.G. Hinson updated his history. This updated history reads very close to the original, and in fact, it was assumed to be a copy. Closer scrutiny has shown this not to be the case. The update is in ink and is aligned in perfect columns, making it much more legible. The transcription here is from the updated version. To date, a transcription of the original Sketch of James Island does not exist.

I hope you enjoy this piece as much as we do. Maps are one of the archival items from which you tend to learn something new every time you read it. This one is no exception.