Waterfowling in South Carolina

Numerous species of ducks and other local waterfowl are central to the Lowcountry’s historic culture, their meat and feathers filling specific desires from dining tables to fashion statements, and even indigenous sacred ceremonies. These birds today still carry a certain mystique all their own, influencing artisans and artists alike with their serene demeanor and brilliant plumage. Even hunting them has become somewhat of an art form. Handcrafted decoys, for example, have themselves become prized pieces of American folk art.

Native Americans fashioned waterfowl decoys as early as the tenth century and were a crucial part of their hunting practices. European settlers, who later interacted with the Native American waterfowl hunters and trappers, observed the astounding effectiveness of what were often quite rudimentary decoy rigs such as duck skins wrapped over floating logs or mere stones arranged to look like a wading bird. Most waterfowl (ducks especially) are “gregarious animals” and will collectively flock to peaceable areas to feed or mate. Hunters thus learned that decoys presented an effective, albeit falsely secure, setting attractive to passing birds.

Mason Decoy Factory, Detroit, Michigan

Used by former Charleston Museum Director E. Milby Burton. William J. Mason began carving decoys in the late 1880s, but by 1903, his son, Herbert, was mass producing them using machinery and assembly line-style techniques which employed dozens of turners, painters and assemblers. The Mason Decoy Factory closed in 1924.

By the late nineteenth century and into the twentieth century, commercial (or “professional market”) hunters capitalized on North America’s abundance of wild waterfowl (and the nonexistent hunting restrictions placed upon them) and took to ponds, swamps and marshes, including those of the surrounding Lowcountry. Using scores of waterfowl decoys in tandem with low-profile “sneak boats” and large-bore weaponry such as battery guns and punt guns (some of which fired one full pound of bird shot in a single blast), market gunners were capable of harvesting several hundred birds, sometimes all in a single day’s work. High demand from city markets for fresh game and bright plumage further drove these commercial hunts, which contributed to the extinction of entire species such as passenger pigeons and Carolina parakeets.

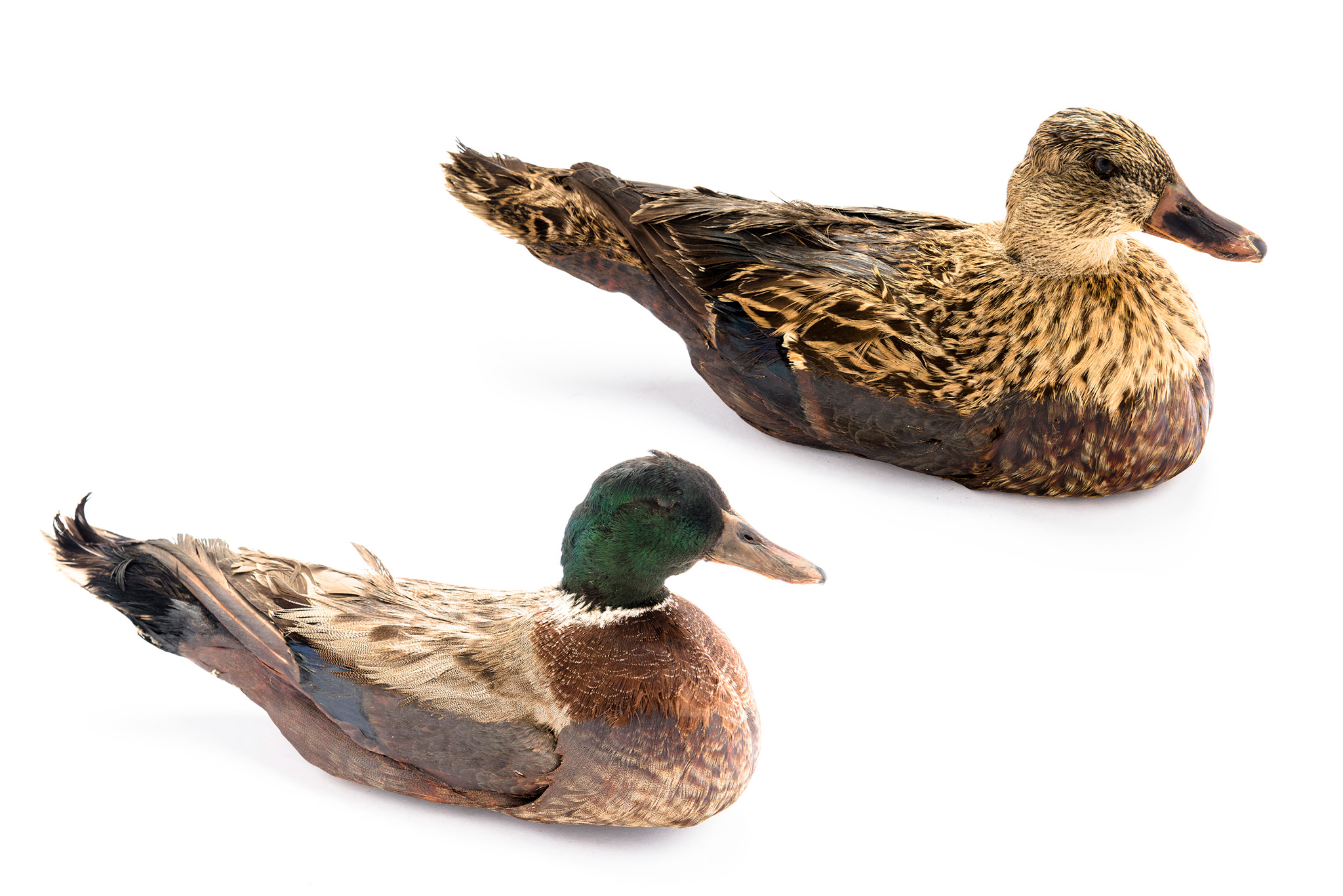

“Specimen” decoys, c. 1930

Whistler Brothers, Morrison, Illinois

Drake and hen mallard decoys are typical of the specimen (or taxidermy) decoys popular during the Great Depression era. Made from farm-raised mallards the skin and feathers of each were wrapped around cork bodies treated and rubberized. Lead weights were added to the undersides to allow the decoys to float upright.

These large-scale hunts drove the manufacture of both handcrafted and cheaper, factory-produced decoys. Strater & Sohier, a Boston manufacturer, for example, began producing foldable, tin-pressed snipe decoys around 1880. Popularly known as “tinnies,” retailers sold them by the dozen. A bit more lifelike were the mallard decoys made by Whistler Brothers of Morrison, Illinois around 1930. Packaged in large metal cases, these sets (six drake and six hen) were specimen/taxidermy style decoys popular during the Depression era. Made from farm-raised mallards, the skin and feathers of each were wrapped around cork bodies, treated and rubberized.

Snipe decoys, c. 1895

Strater & Sohier, Boston, Massachusetts

Known as “tinnies,” retailers sold these snipe decoys by the dozen beginning in the late 1870s. Stamped from tin and designed for portability, each decoy when in use was folded over and mounted on a stick. Though other companies attempted similar designs after Strater & Sohier’s 1874 patent expired, none were as successful.

Large-scale commercial manufacturing of decoys notwithstanding, many master craftsmen during this time continued to expertly hand carve and hand paint decoys. Even today, South Carolina master woodcarver Tom Boozer continues to handcraft hollow-bodied duck decoys using locally grown Atlantic White cedar. He still uses late nineteenth century hand tools to fashion all of his decoys, creating varieties of duck species or, as he puts it, “anything that flies in the Atlantic flyway.”

The Museum’s current exhibit, Feathers and Flocks: Waterfowling in South Carolina, sponsored by the Charleston Mercury, draws from a number of different categories in the Museum’s vast collections as well as a few private ones and presents a collective look at the historic art and artifacts associated with local waterfowling. Open now through May 7.