Downtown Flooding

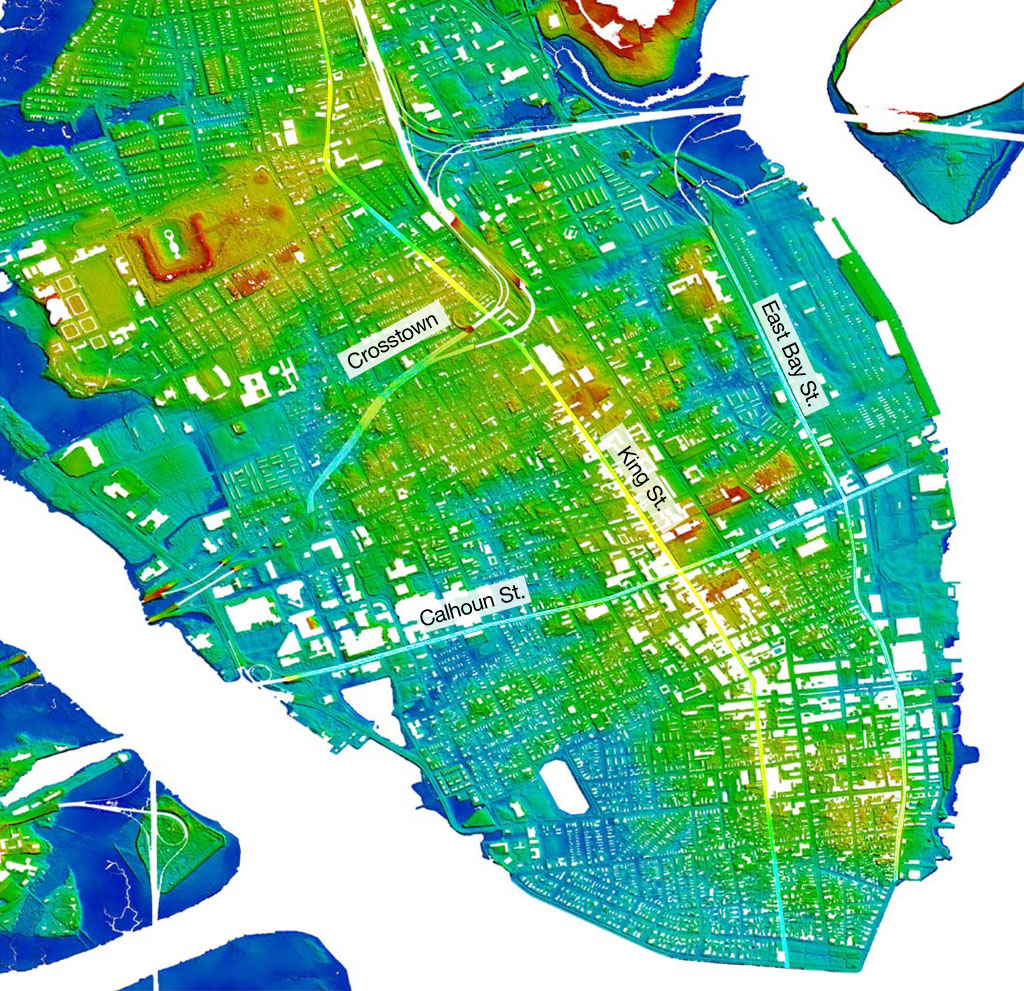

Have you ever wondered why downtown Charleston can sometimes get such horrendous flooding? Anyone who has had to drive through deep ponding on downtown streets surely has. A Museum staff member’s minivan literally floated in one of these floods! The answer lies in the natural history of the area. Long before people settled in Charleston numerous tidal creeks from the Ashley and Cooper Rivers cut into the peninsula formed by these two rivers. The historic landscape can be seen in the “LIDAR” map above. LIDAR is an acronym for “light detection and ranging” and consists of pulses of light directed at the ground from above to measure distances to the Earth. The red areas represent the highest ground on the peninsula, yellow next highest, green next, and light blues represent the lowest possible ground. The rich blue denotes the waterways that currently surround Charleston.

A look at an historic map of the Charleston peninsula shows that the tidal creeks present in the early settlement of Charleston correspond very closely to the light blue areas of the modern LIDAR map. So where did the tidal creeks go? Over time as the city’s population grew in the 18th and 19th centuries, there was a need for more space to live and work. Charlestonians filled in these waterways with trash, discarded brick, pieces of old buildings, ship ballast, and various other debris to provide more living space.

Area bordered roughly by Jonathan Lucas/Barre, Cannon, Coming, and Bull Streets as shown on LIDAR map.This area included one of the largest tidal creeks that cut into the peninsula well into the nineteenth century. Today, with heavy rain and a high tide some parts of this area are prone to flooding. The tidal creek is shown clearly in the accompanying 18th century map related to the Siege of Charleston. Spring Street and Cannon Street, constructed on higher ground, represent safer ways in (Cannon) and out of the City (Spring) during flooding.

Although the creeks were filled in, they still represent the lowest areas of the city. When heavy rains fall over several hours, especially combined with a high tide, the laws of gravity require that water flow to the lowest point. If the water cannot run off fast enough, it soon inundates these depressed areas, often creating very deep pools. Unfortunately some of these places are on major thoroughfares such as Calhoun Street, East Bay Street and the Crosstown.

The City of Charleston has made significant improvements to the underground drainage system over the years and has long-term plans for further work, but only so much can be accomplished when facing Mother Nature and the laws of physics. Ultimately, water will almost always win. Interestingly, the Native Americans who lived in the Lowcountry prior to the arrival of Europeans avoided settling on the lower Charleston peninsula. They may have been on to something.

Area bordered by Charlotte, Meeting, Mary and E. Bay Streets as shown on LIDAR map.The area in dark red at the bottom of this detail immediately above Charlotte Street includes Wragg Square and the grounds of the 2nd Presbyterian Church, one of the highest points on the Charleston peninsula. A crucial part of the American defense line during the Revolutionary War was constructed along this natural “high ground.” Note that The Charleston Museum sits atop a former tidal creek. During the British siege of the city in 1780, this creek fed a moat that ran across the peninsula directly in front of the American lines.

– Director Carl Borick

Thanks to Dr. Jon Marcoux, of Salve Regina University in Newport, Rhode Island, for his assistance in providing the LIDAR map.