The Story of the Charleston Whale

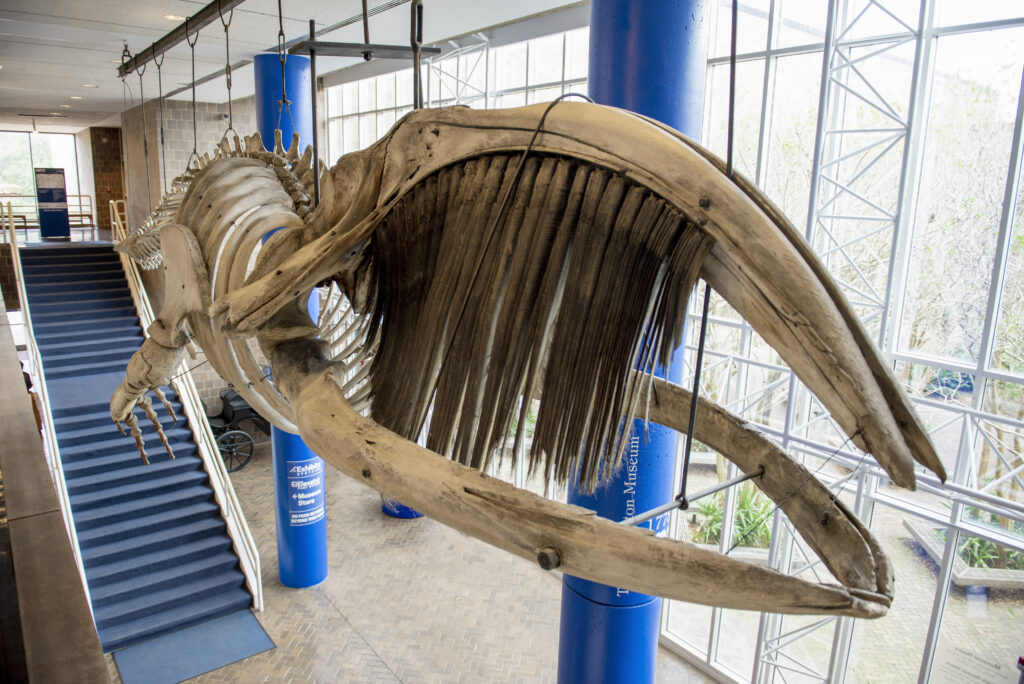

The Charleston Museum has many exhibits which have become fixtures in the minds of visitors. Items and creatures that spark the imagination and leave a lifelong impression. Few have been leaving such an impression as the North Atlantic right whale that hangs in the Museum’s lobby, as it has been a feature of the Museum since it was acquired by then curator Dr. Gabriel E. Manigault in 1880.

The story of the collection of this whale is a snapshot in the changing mentality of how we treat these creatures. When this adolescent made its way into the harbor on January 7th, 1880, it instantly piqued the interest of the local Charlestonians. Although right whales migrate along the eastern coast of the United States, to have one make its way into the harbor was unheard of. Many took to their boats to pursue the animal, at one point amassing a fleet of 60 or so seacraft ranging from rowboats to tugboats, all to be a part of the spectacle.

Although whaling is not really a feature of Charleston commerce, the prospect of killing the animal for its oil was likely a factor for it being hunted so fervently. However, as a consequence, tools for efficient whale hunting were likely not locally available. Instead, many of these “whalers of convenience” utilized whatever they had on hand. Records indicate that many used improvised spears and guns, which due to not being manufactured for the task, likely extended the hunt longer than it would typically be.

Eventually, the whale succumbed and was collected as well as exhibited. Onlookers could come see the animal for twenty-five cents. After it had made its rounds across the city, the specimen was acquired by Manigault for preparation and permanent exhibition.

Today, whaling is no longer a factor affecting North Atlantic right whales. Right whales are a protected species but unfortunately their numbers never rebounded from the impacts of whaling. It is estimated that the entire population of North Atlantic right whales is less than 350 individuals. Like other whales, a lot of their decline is tied to changing global temperatures as well as having their lives disrupted by human activity. These two factors have begun to work in tandem as warming temperatures have pushed the whale’s prey into areas where they are more likely to come into contact with human ships leading to vessel strikes or the animals becoming entangled in fishing nets.

Matthew Gibson

Curator of Natural History