Toys from the Attic

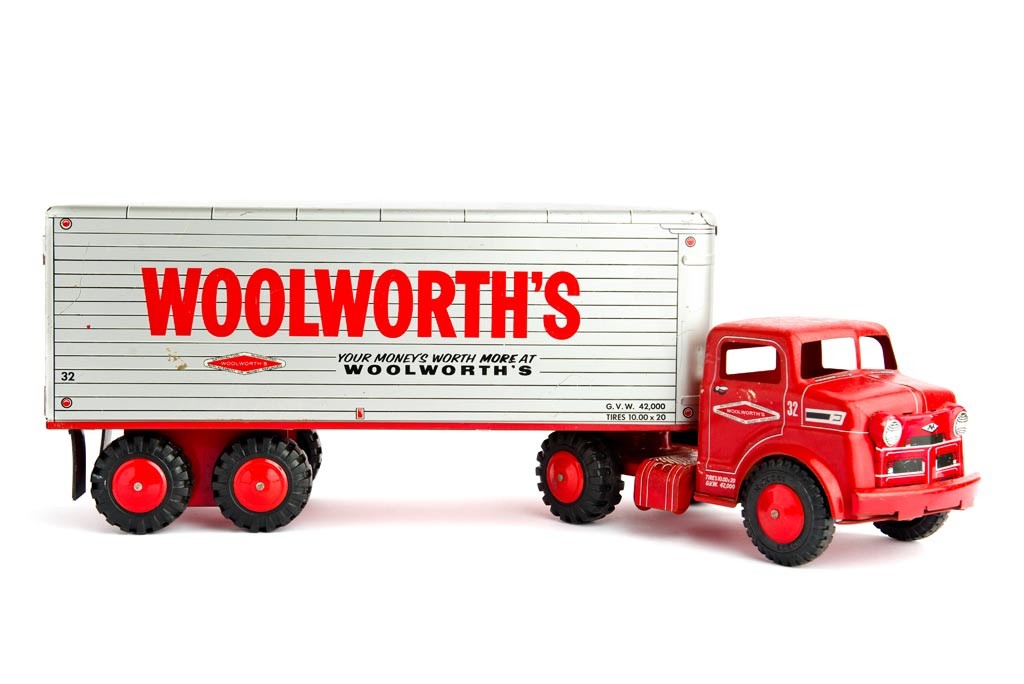

Toy truck, c.1947

Cast metal Woolworth’s toy delivery truck; Purchased at Woolworth’s five-and-dime store on King Street as a gift to Tom Waring.

Whether educational tools, social stimulants or just mindless time killers, toys by their very nature remain an entertaining, albeit incredibly varied, lot and, unlike some other material history, appear in every culture from every era. For those assorted pieces that survive from Charleston’s past centuries, locally made or owned toys present an invaluable insight into what was only recently a vastly understudied genre. Like now, children even in their earliest stages were immersed in a “public and interactive communal culture,” and their toys usually attempted to serve some meaningful purpose in interpreting this environment. To be sure, not even Plato could argue against playtime endorsing it as a means to a youngster’s comprehension as well as his or her own physical growth. The Carolina colonists were no different. Intending for her toddler son, Charles Cotesworth, to “play himself into learning,” for example, Eliza Lucas Pinckney gave to him a “sett of toys to teach him his letters by the time he can speak.” Though what exactly those toys actually were was unsaid, Eliza’s effort to develop Charles’s cognitive behavior is certainly evident.

Toy soldiers (sides) and chess piece (middle), 1760-1780

Excavated from the Heyward-Washington House (89 Church Street), the chess piece was molded from clay while the toy soldiers and made from tin. Traces of red paint appear on the soldiers’ breeches with blue on their coats and hats.

Unfortunately, when examining toys and their vast subcategories from a historical prospective, their whimsical amusement can – and many times does – turn to anything but. Most of Charleston’s children living before the 19th century’s latter half couldn’t just run down to the corner toy store and peruse the shelves. In fact, only seldom did a local shopkeeper even advertise the making of toys, and even when they did, it appeared as a mere secondary, supplemental service. One “E. Smith,” for example, a local wood turner “From London,” advertised via April 19, 1796 City Gazette and Daily Advertiser that his Tradd Street shop could turn “all kinds of work…both in hard Wood and Ivory; likewise turns all kinds of Metals, Walking Canes, Umbrella handles, Billiard Balls, Children’s Tops, and every other Article in the Toy or Fancy Way…made in the neatest manner.” Thus, most toys made prior to the 1850s were one-of-a-kind items made on demand with readily available materials such as wood, paper, iron, lead or tin. Moreover, a vast majority were homemade without any sort of clue as to its maker – or even original user.

Marbles

Myriad styles and period marbles were excavated from the Miles Brewton House grounds between 1988 and 1991. From left to right: Plain gray and brown clay (late 18th century), undecorated and hand-painted glass (mid 19th century), brown-glazed Bennington (1870s) molded glass (early 20th century).

To this end, archaeological excavations play vital roles in uncovering the playtime attributes of long gone local children. Although the more expensive, sentimental toys such as silver baby rattles were often preserved for generations within a single family, other more practical toys like marbles, dolls and game pieces made from organic materials such as glass, porcelain or bone are commonly found amid local archaeological sites. Of course, these items typically turn up broken having been discarded in the yard (excavations around the grounds of both the Heyward-Washington and Miles Brewton House produced all three), but this is hardly surprising since toys were designed to be played with and simply wore out.

(Left) Baby rattle (or, “coral and bells”) c. 1750

Coin silver body with attached bells and whistle at the top; coral handle was used for teething. The use of coral on baby items was moderately popular in the 18th century as it was believed to help indicate health – a deep orange or red when healthy, a paler shade “when illness threatened.” Evidence of gold leaf appears on each bell. English origin.

(Right) Top, 1750

Used for games similar to “Put and Take,” the turned and carved ivory top is engraved on four sides with letters “H, N, P, T.” (H for take half, N for nothing, P for put in, and T for take.) Children would often use marbles or beans while adults used coins.

Eventually, alloys, synthetics and machinery of the post-Civil War era ushered in a new wave of inexpensive, mass produced toys, and although items made in these subsequent years provide better, durable and certainly more easily identifiable data, the uniqueness, technology and artistry of antebellum and colonial toys all but vanished.

Steam-train engine, c.1865-1870

Rudimentary train engine formed from tinplate and cast iron wheels.

American manufacture (attributed), From the estate Emily S. McCrady, Charleston.

To their credit, however, within this new generation of toys came renewed fervor in recreation for both young and old. By 1880, the US Census Bureau listed 173 toy and game manufacturing companies all competing against one another for the latest and greatest plaything. Spring- and friction-driven mechanics put toys into motion while bells and whistles provided sound effects. Colors and intricate details became just as important to toys as their function. One maker advertised dollhouses with “lithographed wallpaper,” another announced toy boats with “working steam engines,” and Milton Bradley was actually reprimanded by the Feds in 1892 for making toy money that was “too realistic.”

Fantascope, c. 1833

With the illustrated paper disk in place, the user would spin the disk while looking through its apertures and into the mirror. The spinning motion created an animated scene in the mirror. Made in London.

Though non-local manufactories provided most articles for Charleston’s toy market in the early 20th century, area retailers did well in keeping their shelves stocked. General merchandisers all along King Street like Edwards 5&10 and, of course, F.W. Woolworth soon dedicated entire sections of their stores for toys and games with Legerton & Co. once located at 263 King being among the first local operations to specifically advertise toys for sale in Charleston’s city directories.

Of course, this year’s holiday season will doubtlessly see computer-driven technology like video game consoles and tablets sitting squarely atop most wish lists, but there will always be room for the basics, or so goes the adage: the more things change, the more they stay the same.

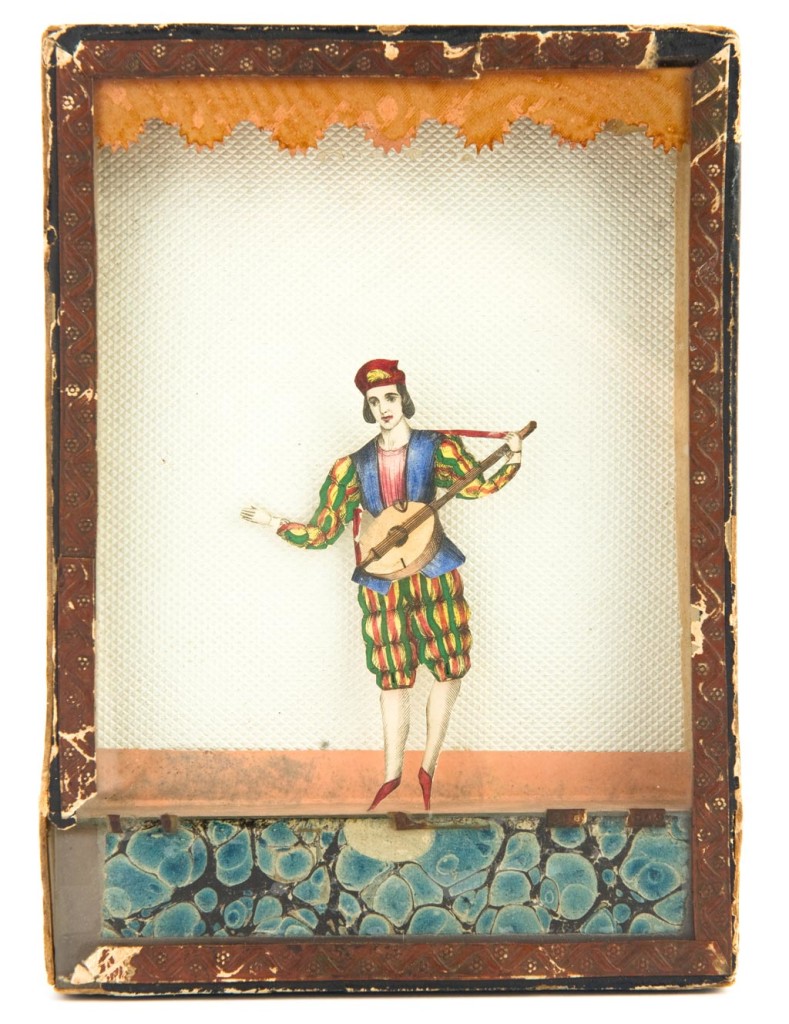

Sand toy, c.1857

An hourglass-styled, sand-filled container is enclosed in the back section of the box. When rotated and positioned upright, the falling sand spins a miniature paddlewheel which in turn bounces and moves a small pin attached to the dancer’s back. As the pin moves, the dancer jumps up and down, his hinged knees and legs jostling about. Handwritten inscription on the reverse side reads, “For Arthur, from Aunt Maria / Dec. 25, 1857.”

This article, written by The Charleston Museum’s Chief Curator, Grahame Long, was originally posted in the Charleston Mercury’s winter edition magazine in 2013.