The Mummy of The Charleston Museum

For many years, mummies have evoked a sense of the macabre. Illustrated as lumbering, linen-wrapped figures stumbling toward its victim with outreached arms, they have become a symbol for monsters in horror movies and gothic fiction. However, mummification for ancient Egyptians, was a respected and honored tradition that lasted for well over 2000 years.

Although mummification varied throughout the Dynasties, depending upon the price paid, the general process took seventy days with specialized priests performing rituals and prayers. First, the brain was removed in bits, by inserting a hooked tool through the nostrils. Next the priests, or embalmers, made a cut in the lower left side of the body to pull out the organs contained in the chest and abdomen, leaving only the heart. Each organ was persevered separately in special canopic jars that would later be buried with the individual. The embalmers would then cover the body with a type of salt called natron to remove all of the moisture. This resulted in a dried out, but very recognizable, human appearance. After this, the wrapping would begin.

Taking long strips of linen, some written in prayers, the priests would wrap the body, being careful to wrap each finger and toe individually. To further protect the dead, amulets were also placed within the strips of cloth. A warm resin was used to coat the form in between wrappings and when the ritual was finished and the body completely wrapped, a shroud was placed on top and tied with linen strips.

Lady of Cairo, c. 700-30 BC

The mummy of The Charleston Museum is a woman thought to be between 20 and 40 years of age. She was taken by a Bedouin sheik from a tomb in Cairo and sold to Horatio G. Wood, American Vice-Consul in Egypt, of Rhode Island. Curator Gabriel E. Manigault purchased the mummy from Woods for $200 in 1893.

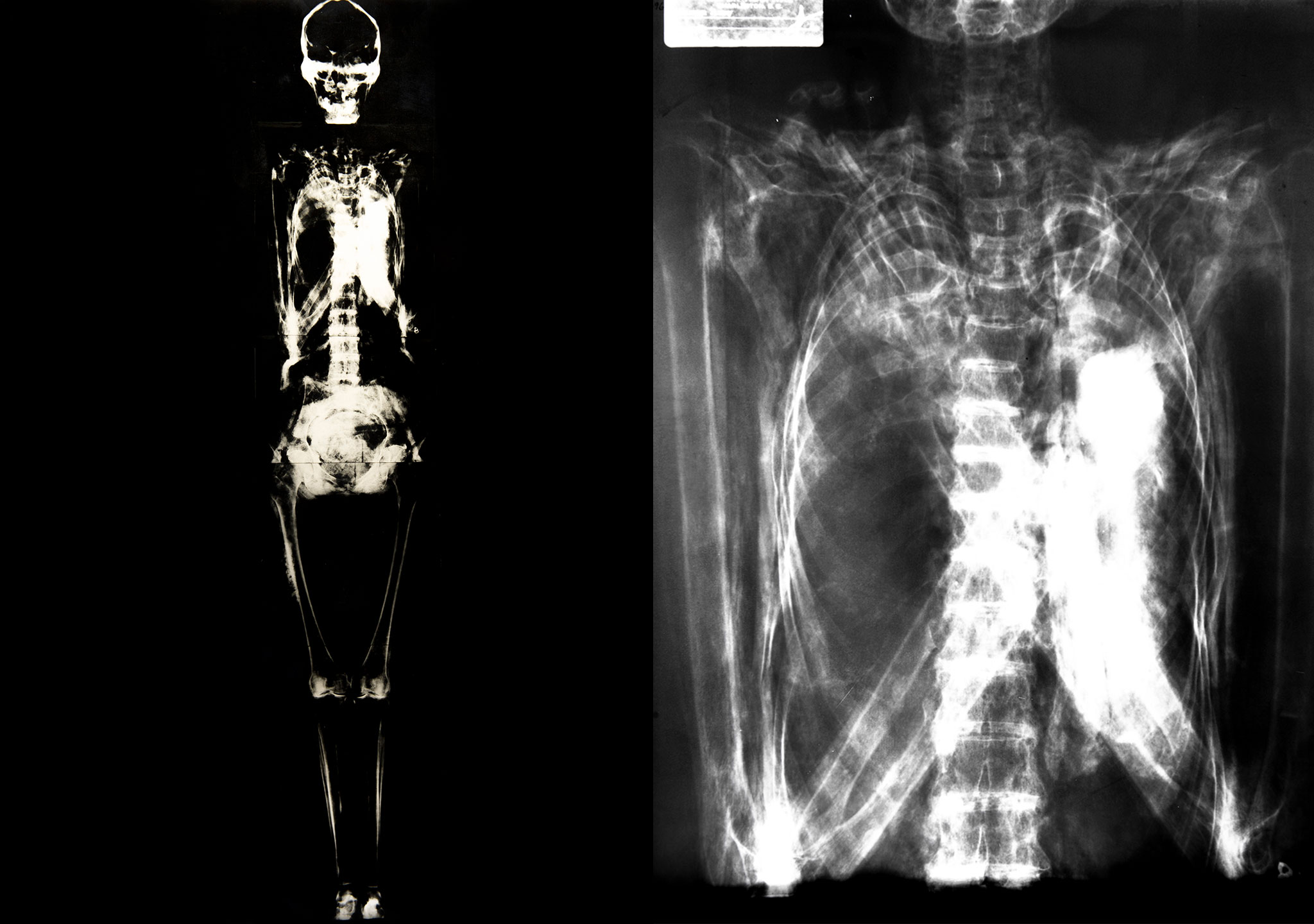

The toes are individually wrapped, the arms are crossed and the body is partially filled with resin. X-rays show fractures in the left 6th rib and the mid-shaft of the right clavicle, both with no evidence of healing, indicating they were broken after death, most likely during the embalming process. The chest contains a large double roll of material, possibly the funerary text of prayers or spells intended to aid the dead in their journey through the underworld, or Duat.

The facial wrappings were removed when there was doubt as to whether or not “…human remains were there.”

Present day researchers in the field are continuing to study mummies and what lies beneath the wrappings.