The Grimké Sisters

The Heyward-Washington House, Abolition, & Image Creation

The exhibition case featuring the Grimké Sisters in The Charleston Museum.

In its 250 years standing on Church Street, one of the most impactful occupants of the Heyward-Washington House may have also been its youngest: Sarah Grimké (1792-1873). She and her sister, Angelina Grimké Weld (1805-1879), would go on to become abolitionists and feminists, writing and delivering speeches on behalf of both causes in speaking tours across the northeast United States. Notably, a set of daguerreotypes and a set of wood engraving portraits of both sisters survive. Historic images allow present day people to associate a face with their words, and know what these two women looked like – perhaps. 19th century portraits are a valuable resource for analysis and understanding, but can be deceptive. So what do we actually know about what the Grimké sisters looked like, and what they would have worn?

The Grimké Family lived in the Heyward-Washington House from 1794 to 1803, when Sarah was ages 2-11, and before Angelina was born in 1805. Their father, John Grimké, had fought in the Revolutionary War before becoming a judge, and their mother, Mary Smith, was from a wealthy and well connected Charleston family. The Grimkés did not just participate in, but reinforced the structures of enslavement, including meting out cruel mistreatment for infractions. One such punishment of an enslaved woman was a formative memory for Sarah Grimké, who at the age of four witnessed a whipping. Grimké’s posthumous biographer, family friend Catherine H. Birney, notes that Sarah then tried to run away and was later found down on the wharf, trying to seek passage somewhere “where such things did not happen.” The enslaved woman who had received the brutal beating is not named, nor is her fate brought up again, either due to Sarah’s young memory, or a lack of later knowledge.

This incident would likely have taken place in the work yard of the Heyward-Washington House, marking it as a site of a savage moment of history that also served as a catalyst for change. Sarah Grimké could never quite reconcile herself to the system of slavery, even as she grew up mired within it, and as god-mother to her younger sister Angelina, 13 years her junior, she was a steady influence against the institution. Both would go on to leave Charleston for Philadelphia in the 1820s, and trade in their Episcopal Christian upbringing for a Quaker Meeting, with Sarah leading the way and Angelina following.

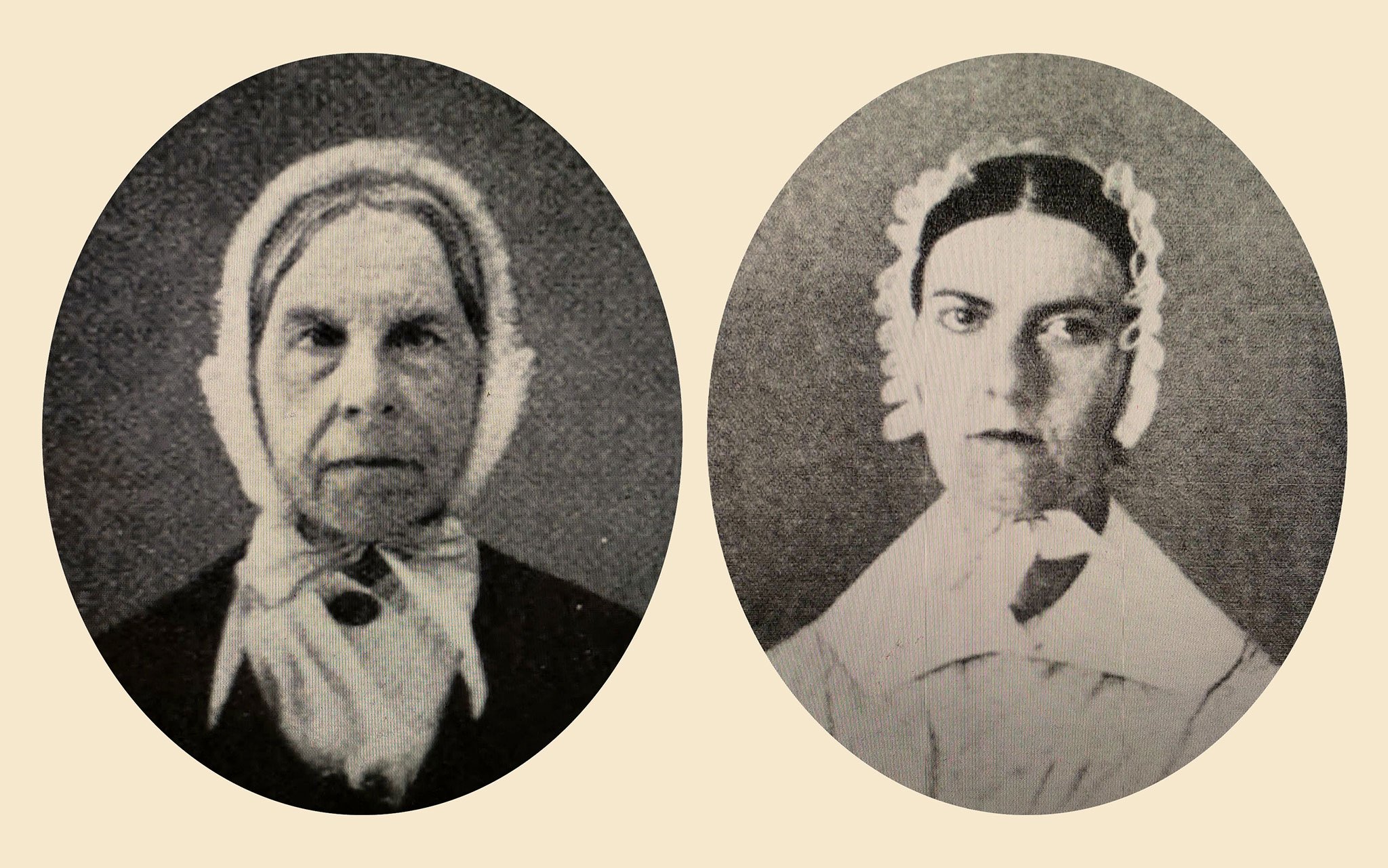

Sarah Grimké & Angelina Grimké Weld. Daguerreotypes from the 1840s, printed January 1910, American Magazine. Article by Ida Tarbell. Vol. 69, no. 3.

Images of both Grimké sisters are preserved in a set of daguerreotypes created in the 1840s and notably published by journalist Ida Tarbell in a 1910 edition of American Magazine. However the subsequent wood engravings based on these portraits are the more widely circulated images of the two sisters today, likely due to ease of access from their repository in the digitized collections of The Library of Congress.

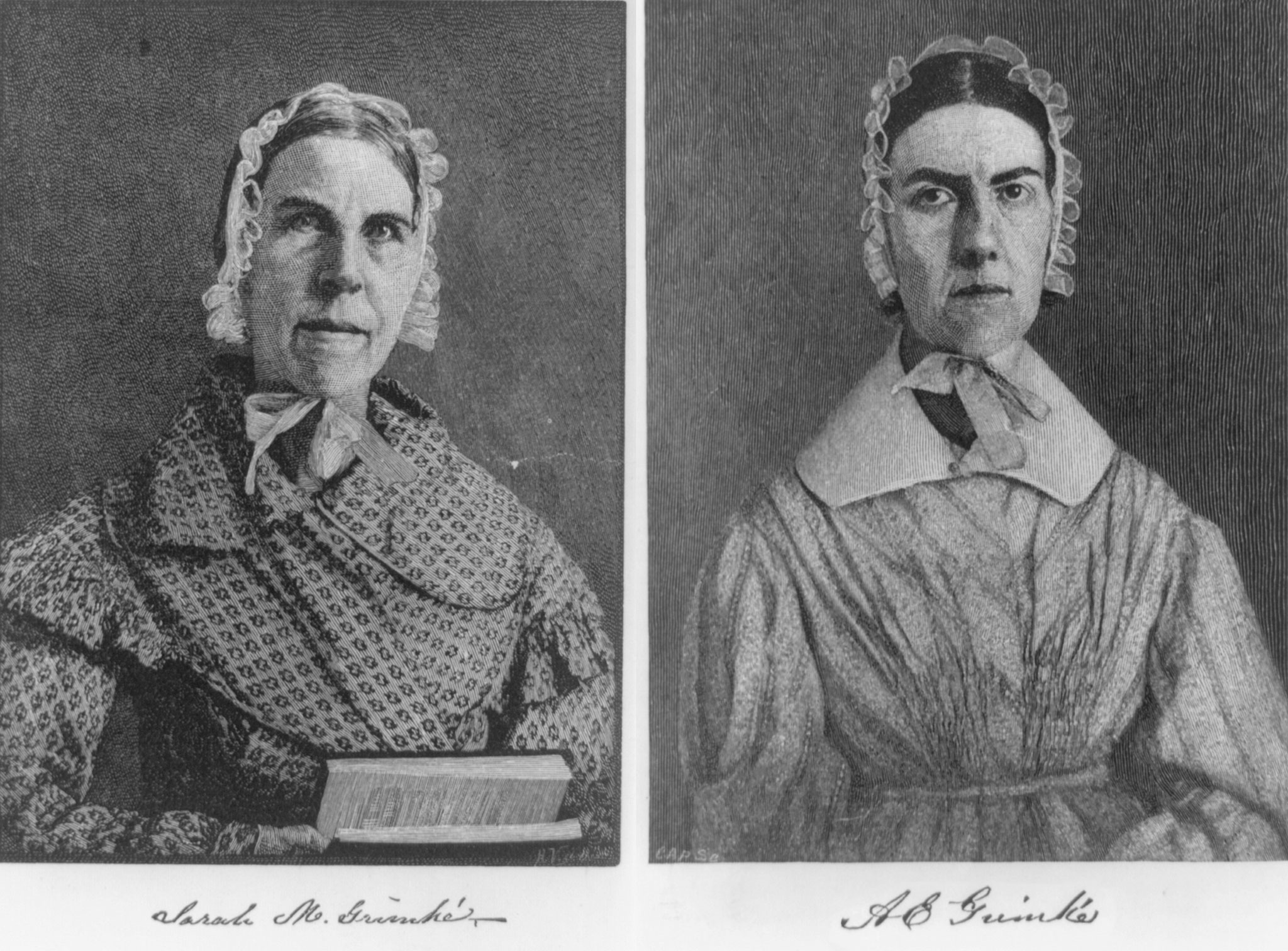

Sarah Grimké (1792-1873) and Angelina Emily Grimké (1805-1879). Wood engravings from the Collections of the Library of Congress.

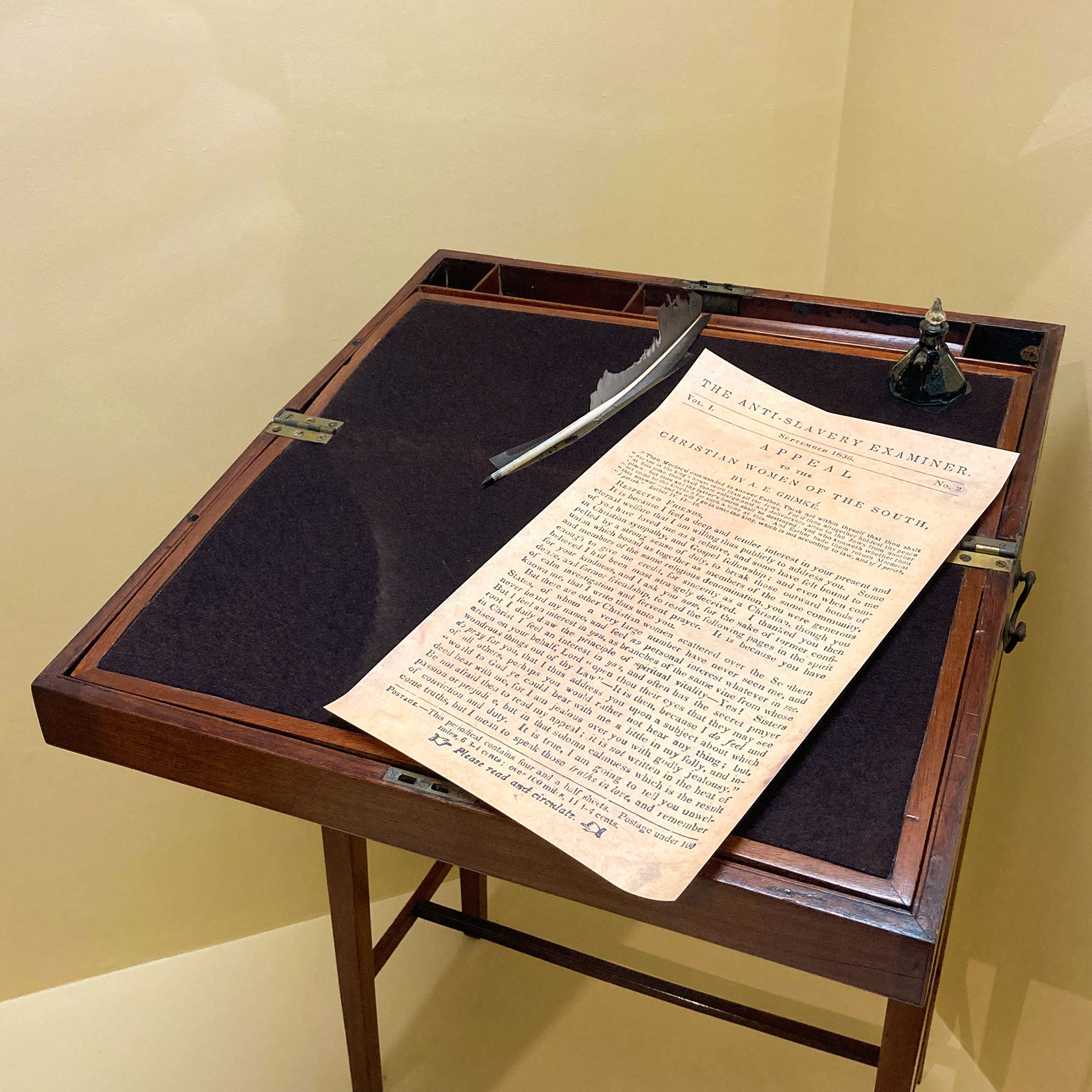

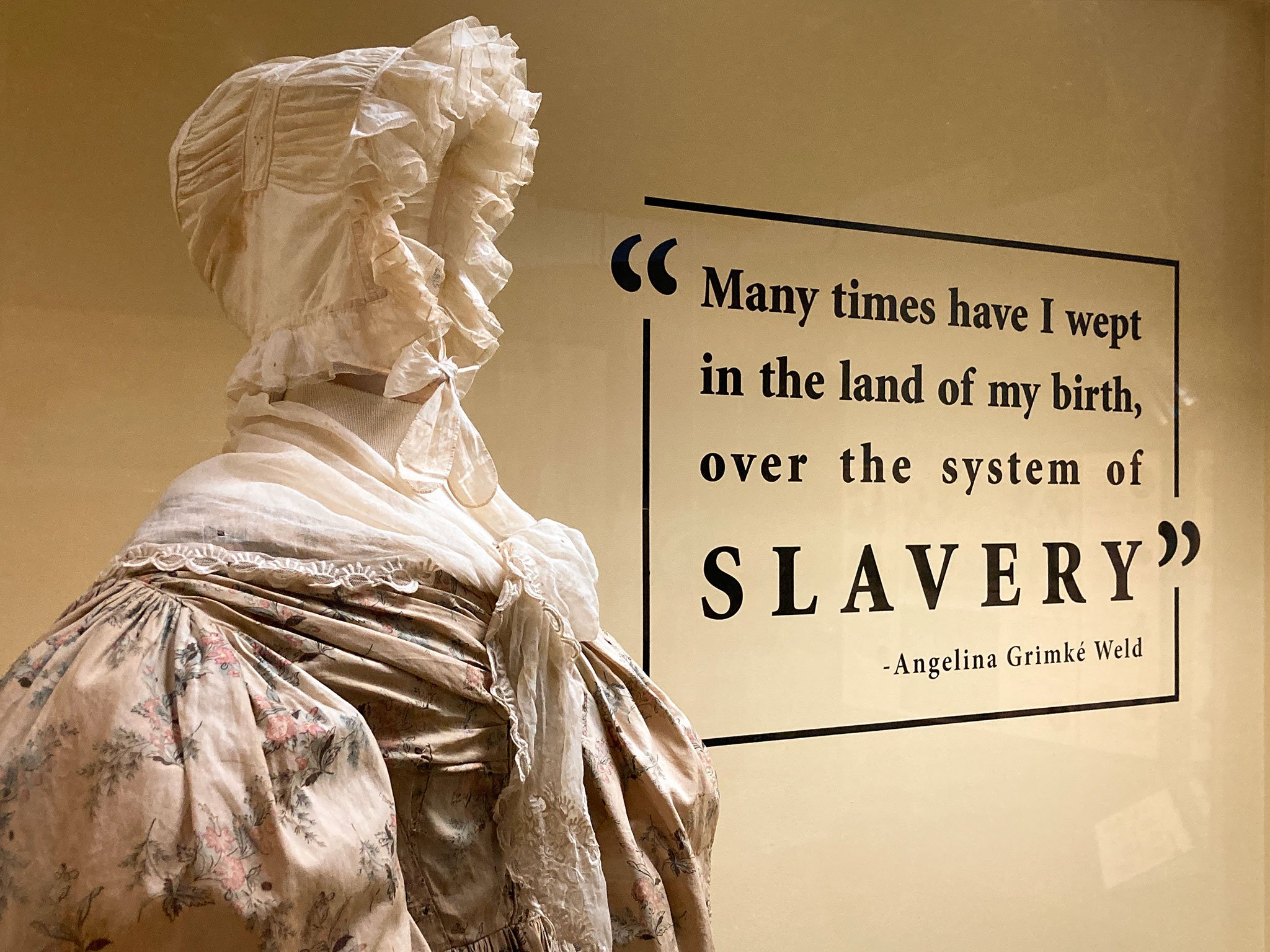

In finding ways to represent the Grimké sisters and their connection to the Heyward-Washington House within the museum galleries, these portraits served as a jumping off point for a new exhibit. Their presence has been recreated through a mannequin dressed in clothing from the Historic Textiles collection, including a ruffled cap in the style worn by the sisters in both portraits. Dresses from the 1830s and 40s will rotate on display, since Angelina’s most famous abolitionist publication, “Appeal to the Christian women of the South” was produced in 1836, and the portraits show garments common to fashions of the 1840s.

A writing desk with a reproduction of Angelina Grimké’s 1836 publication, “Appeal to the Christian women of the South.”

By this time, both sisters would have been professed Quakers for more than a decade, but were cast out of their Meeting for Angelina’s marriage to a non-Quaker, Theodore Weld, in 1838. So it is interesting to note that both wear patterned dresses in their portraits. Quaker “plain dress” is often misunderstood in the context of popular culture, but in this period it is true that most Quakers discarded more obvious fashion trends in favor of simpler clothing. Sarah Grimké originally viewed plain dress as a means of humbling herself, writing in her diary “I changed my dress for the more plain one of the Quakers, not because I think making my clothes in their peculiar manner makes me any better, but because I believe it was laid upon me, seeing that my natural will revolted from the idea of assuming this garb.” This did not mean cheap or ugly garments – a Quaker woman might satisfy the requirements of “plain dress” with a very simple textile that was made from pure silk of very high quality. The more austere Quakers might wear only single tone fabrics in dark colors, but there was variation from group to group. Despite no longer officially being part of that faith, Angelina and Sarah have still opted for simple attire when compared to women’s fashionable dress in the 1830s and 40s, which could have an exaggerated silhouette with large sleeves and a lot of accentuated detail.

Beyond what the two women are clothed in, proper art historical analysis of the portraits has to include the dour expressions of both sisters. Since the wood engravings were likely later created from daguerreotype originals, it’s not surprising that the Grimkés might look stern. This was not uncommon for the mid-19th century, when creating daguerreotype images required steady long term exposure, and holding a smile was too difficult to capture. The sisters might have even desired to look serious, as a credit to their working personas as authors and lecturers.

Yet it’s important to consider how the sisters are portrayed in the context of their work, and the world of image making as it shifts influence. These wood engraving images could have been more widely distributed through printing than the original daguerreotypes. This would have been consequential for the sisters’ reputations, since having an image of yourself, whether painting, daguerreotype, or engraving, was still a rare occasion of note. In a time period when only the written words of the sisters would have been distributed widely, and recordings of their speeches could not yet be made in either sound or video, image mattered. This is one reason that the formerly enslaved abolitionist Frederick Douglass intentionally had himself photographed often– he wanted control of crafting his own public image as a man of dignity and consequence.

Though the Library of Congress holds the wood engravings as reproductions from a book in their collections, little is known about their origins. Angelina Grimké may be dressed the same in both images, but in the daguerreotype she’s notably softer featured, with a rounder face, lighter eyebrows, and more curved lips. This evidence lends credence to a theory by historian Louise W. Knight – the wood carvings are likely satiric images, produced by someone looking to discredit the sisters’ arguments by portraying them harshly. This tactic was often used to discredit political and ideological opponents, by drawing the argument that if these women were conventionally pretty enough to be desired by men, they wouldn’t espouse such controversial ideas. Indeed, this tired trope can still be found in the comment sections of contemporary feminist scholars working through online platforms today. For Sarah Grimké, who intentionally never married despite several proposals, and for Angelina Grimké, who was married to an abolitionist, it seems to be a misplaced argument, but logic is typically not in play for this form of disparagement.

The original source of the wood engravings may be lost to time, but, regardless, the Grimké sisters are best represented by their written work, which helped to define mid-19th century feminism and abolitionism. The use of the Grimké portraits to establish a human connection to these authors is helpful, but the daguerreotypes and their altered wood engraving reproductions are a quintessential lesson in not judging a book by its cover, and a reminder not to take history at face value. Preservation and analysis of the Heyward-Washington House allows us to continue to evolve our understanding of the past, and serves to crystallize a moment of the legacy of Sarah Grimké in particular, who from a very young age could not tolerate cruelty and injustice.

Virginia Theerman, Curator of Historic Textiles

Select Bibliography

Birney, Catherine H.. The Grimké Sisters: Sarah and Angeline Grimké the First American Women Advocates of Abolition and Woman’s Rights. N.p.: Createspace Independent Pub, 2015.

Grimké, Angelina., Grimké, Sarah. On Slavery and Abolitionism: Essays and Letters. United Kingdom: Penguin Publishing Group, 2015.

Knight, Louise W. “The South Carolina Aristocrat Who Became a Feminist Abolitionist.” Smithsonian Magazine, July 24, 2018. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/south-carolina-aristocrat-who-became-feminist-abolitionist-180969723/.

Knight, Louise W. “Who Were the Grimke Sisters?” Scholarly Blog. Accessed June 22, 2022. http://www.louisewknight.com/about-the-grimke-sisters.html.

Lerner, Gerda. The Grimké Sisters from South Carolina: Pioneers for Woman’s [sic] Rights and Abolition. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 1998.