The Founding of America’s First Museum

This is an exciting month for The Charleston Museum as January 12 marks the 250th anniversary of the founding of a “museum,” that would eventually become the wonderful institution we know today. Comprised of some of the leading learned men of the colony of South Carolina, the Charlestown Library Society was responsible for the creation of this museum. Some of the Society’s members who helped found it, such as Thomas Heyward, Jr., and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, had studied law at Middle Temple in London, and were surely influenced in this new endeavor by their exposure to the British Museum, the two being just over a mile apart.

At their January 12, 1773 meeting, Lt. Governor William Bull, president of the Charlestown Library Society, proposed that a committee be appointed “for collecting materials for promoting a natural History of this Province,” the genesis of the Museum. The Society’s prospectus announced that “taking into their consideration, the many advantages and great credit that would result to this province, from a full and accurate natural history of the same,” they “have appointed a committee of their number to collect and prepare materials for that purpose.” They asked gentlemen, especially those residing “in the country,” to procure and send them “all the natural productions, either animal, vegetable or mineral…with accounts of the various soils, rivers, waters, springs, & c., and the most remarkable appearances of the different parts of the country.”

Accordingly, the Society “fitted up a Museum for the reception and preservation of specimens of these several natural productions,” and appointed Thomas Heyward, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, Alexander Baron, and Peter Fayssoux to receive them, who we can consider the Museum’s first curators.

What was the Society trying to accomplish in this endeavor? The answer is obtained by looking closely at its prospectus. With regard to plants and trees, they asked that the best accounts be given of their uses and virtues, either in agriculture, commerce or medicine. Of the fossils, minerals, ores, soils, clays, marls, sands, and shells, they sought “the best accounts of their several natures, qualities, situation and uses.” They wished to collect and learn more about these resources to further enrich the agricultural and economic success of South Carolina. Simply stated, their purpose was to educate themselves and others, the common thread between the reason for the original museum’s founding and the modern Museum’s mission. Today, the Museum’s collections, exhibits, and programs have a different endgame but the same rationale – so that people can learn.

Pages from the 1798 accessions book, the earliest surviving record of the Museum collections, listing donated objects.

Courtesy of the Charleston Library Society, Charleston, S.C.

We will never know what the “gentleman in the country” contributed to those early collections since the Fire of 1778 destroyed them and associated records. We do know that collecting resumed by the 1790s and the Museum was located on the third floor of the State House, now the Charleston County Courthouse. The institution, had strayed from its initial South Carolina focus, however, as evidenced by the earliest known collections records, an accession book in the holdings of the Charleston Library Society. Although acquisitions included a “beautiful species of spider” caught by Thomas Branford Smith on his piazza, most of the remaining objects came from other parts of the world. Since Charleston was one of the key ports in the southeast, with goods coming in from every corner of the globe, this collecting trend continued throughout the nineteenth century.

Randolph Hall at the College of Charleston, where the Museum was housed from 1852 to 1907.

The Library Society transferred the Museum collections to the Literary and Philosophical Society of South Carolina in 1815. Under its guidance, the collections continued to grow, and were enhanced by contributions from prominent naturalists such as Joel Poinsett, Stephen Elliott, John Edwards Holbrook, and the Reverend John Bachman. Despite a compelling exhibition of its materials in the 1820s, the Museum still lacked permanency, however, and it moved around the City, including locations on Chalmers Street, Broad and Church Streets, and even a “low wooden building” on the grounds of the Medical College (now MUSC). The College of Charleston eventually acquired the collection and combined it with those of Francis Holmes and Bachman to open the Museum on the third floor of Randolph Hall in 1852, which initiated greater stability. The College’s Trustees appointed Holmes as curator.

According to Charleston’s Daily Courier, this new version of the Museum was popular with local citizens as well as “distinguished naturalists” from other states who came to view its collections. The Civil War put an end to this brief golden age. With federal troops threatening the city, Professor Holmes prudently moved most of the collections to Edgefield for safekeeping, a fortuitous decision since some pieces left behind were destroyed after the Union occupation in 1865.

(left) Gabriel E. Manigault, curator, 1873–1899, oil on canvas by John Stolle, 1894. (right) Museum collections on exhibit at the College of Charleston, c. 1900, including the North Atlantic right whale skeleton that now hangs in the Museum’s main lobby.

The post-Civil War period was a time of economic decline for Charleston, and the Museum fell on hard times. Fortunately, the College Trustees appointed Gabriel Manigault as the curator in 1873. Despite limited funding and a seeming lack of interest in the Museum by the College, he expanded the collections and improved the exhibits. He was responsible for the acquisition of some of the iconic pieces in the collection, including the North Atlantic right whale skeleton that hangs in the Museum lobby, the Egyptian mummy, and the casts of statuary from the British Museum.

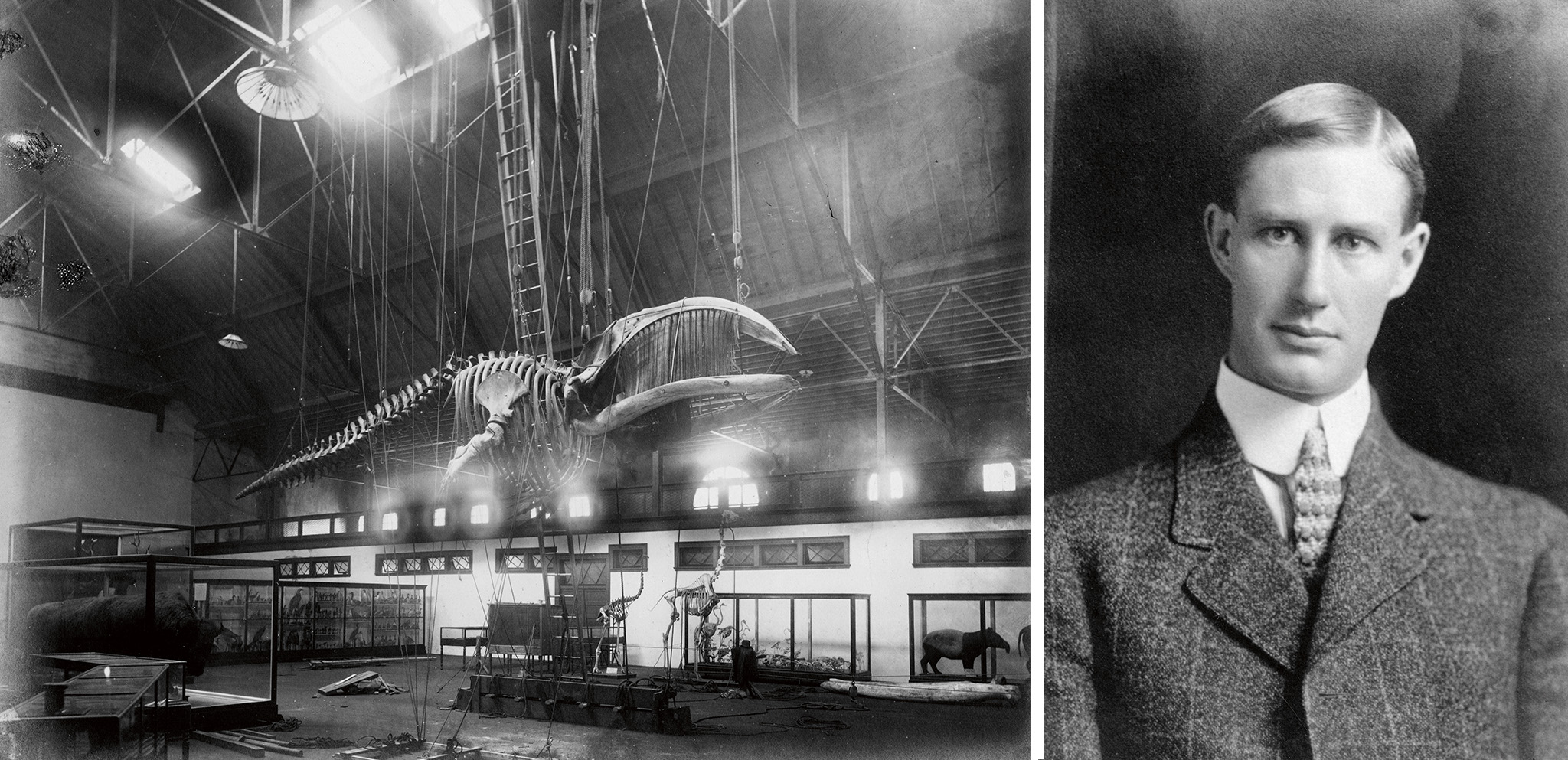

(left) Installation of the North Atlantic right whale skeleton at the Museum’s 121 Rutledge Avenue location, c. 1908. (right) Paul Rea, director, 1906–1920. Rea provided the critical leadership that brought the Museum into the modern era.

After Manigault’s death, the College installed George Hall Ashley as curator but it would be Ashley’s successor, Paul Rea, who would bring the Museum into the modern era. Named the Museum’s first official “director,” Rea oversaw the move of the Museum from Randolph Hall to Thomson Auditorium on Rutledge Avenue, which had been built for a Confederate veterans’ reunion and which would later be affectionately remembered by many locals as the “old Museum.” Rea also spearheaded the effort to make the Museum independent of the College of Charleston, and in 1915 the South Carolina Secretary of State issued a charter for the incorporation of The Charleston Museum, the first time it would be known by that name.

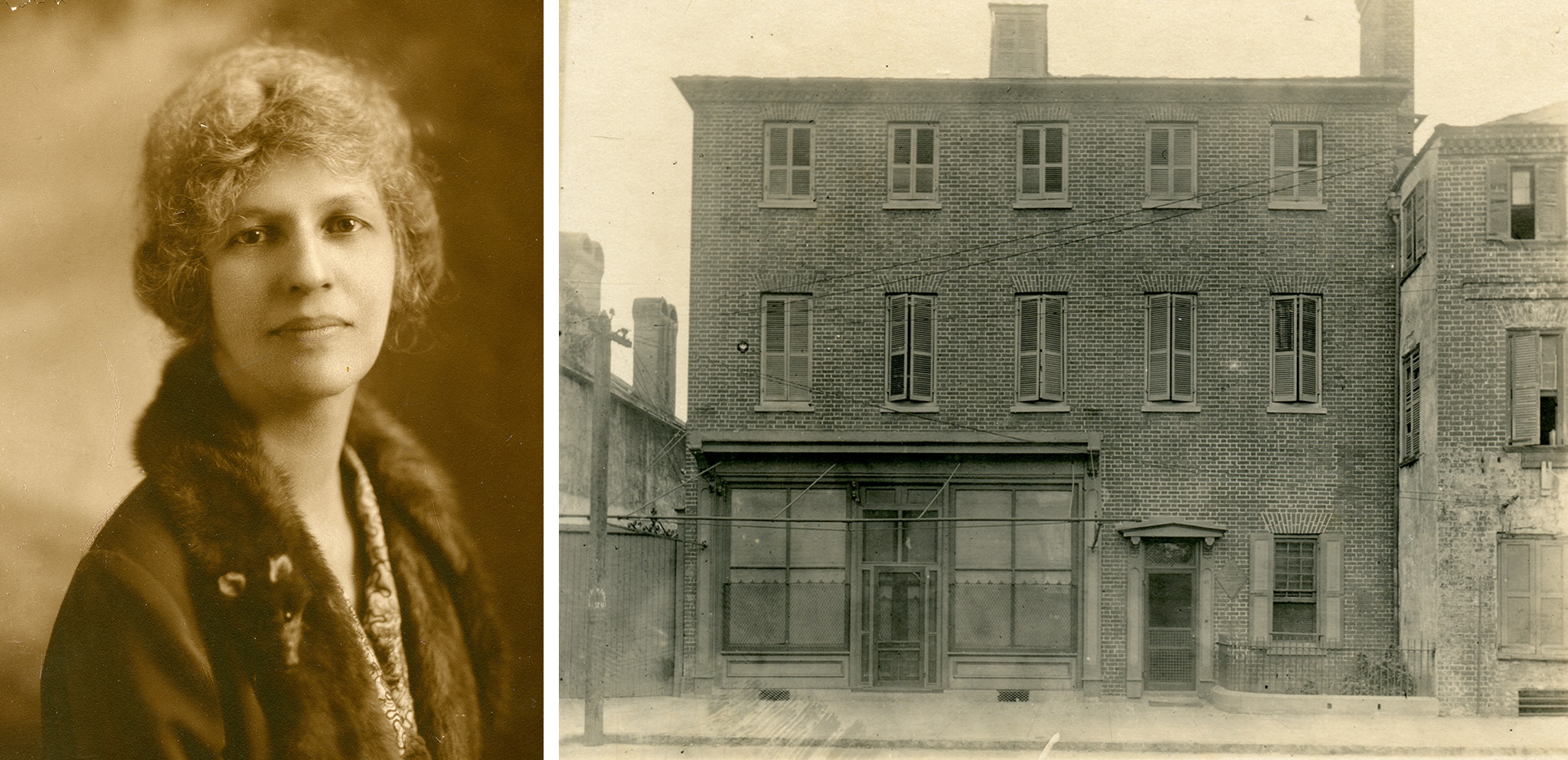

Originally the town home of Thomas Heyward, Jr., the Heyward-Washington House (right) had been turned into a bakery with a storefront in the late 19th century. Director Laura Bragg (left) helped raise the funds to purchase the building in 1929 and return it to its original floor plan. One year later, the first museum created in North America produced the state’s first house museum when it opened the home to the public.

Rea also hired Laura Bragg, who would succeed him as director. Bragg was influential in the acquisition of the Heyward-Washington House and in expanding the Museum’s education programs, which she insisted also be available to Blacks in the era of Jim Crow. She, her successor Milby Burton, and capable administrators such as Donald Herold and John Brumgardt continued to expand the collections and appropriately steward the Museum throughout the twentieth century.

Despite the many transitions that it went through in 250 years, the purpose behind its founding – to educate – would remain. Today, The Charleston Museum, which had its beginnings in the efforts of South Carolina’s wealthy elite, is a resource for learning for people from all walks of life from around our state, the country, and the world.