The Charleston Museum Mahiole – A Case for Reading Exhibit Labels Closely

I am going to make a case here for one particular object in the museum’s collection, on display in the Early Days exhibit, as one of the most interesting objects you could possibly see on a trip to the museum. The Charleston Museum is America’s oldest public museum, initially founded as part of the Charleston Library Society in 1773, and Early Days documents the history of the institution. Among the taxidermy animals and Egyptian artifacts, tucked into a corner in a glass case, is a somewhat innocuous piece of headware. This helmet is brown, a bit plain, and blends in with the other Polynesian objects around it. A small label next to the helmet reads “Chief’s Helmet, Hawaii (Sandwich Islands), Donated by Major Ladson, 1798.”

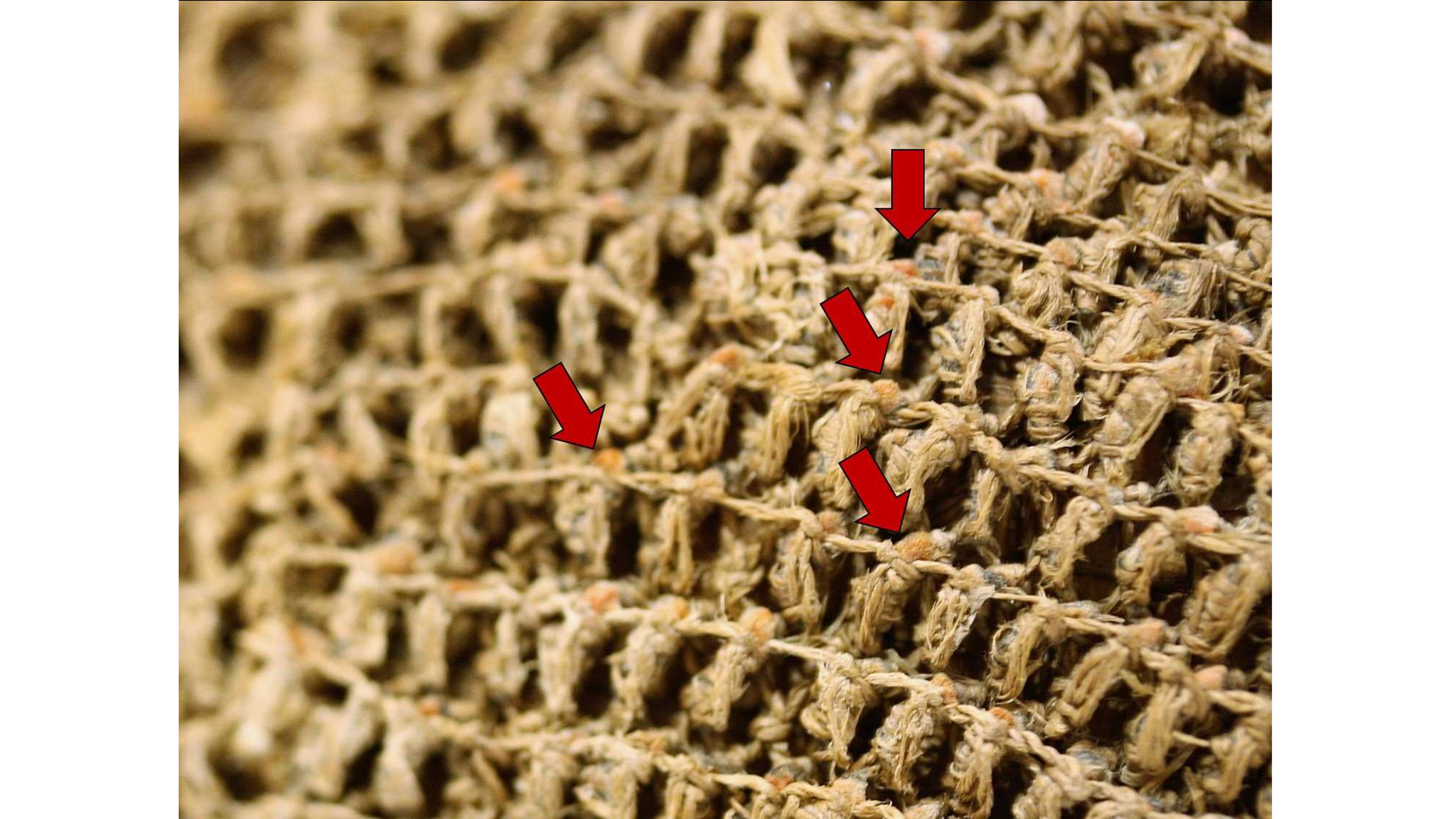

The helmet is actually a mahiole, a symbol of chiefly authority in the Hawaiian Islands, and frequently paired with featherwork cloaks known as ‘ahu ‘ula. This particular helmet has lost its spectacular red feathering to time. But, there is evidence on the object itself that it was once as resplendently adorned as the example from The British Museum. In Hawaii, the aristocratic class wore mahiole and ‘ahu ‘ula during significant social rituals and warfare. The crest of The Charleston Museum’s mahiole suggests it may have once have belonged to or was intended for, a high chief or king.

With an accession date of October 1798, the helmet is considered the museum’s earliest gift. The James Cook expeditions first made contact with the Hawaiian Islands in 1778. That is only twenty years for the mahiole to travel half a world away, in the age of sail and well before the existence of the Panama Canal, and arrive in Charleston. This leaves us with a limited number of routes by which the object could have reached the city. The first potential way is the helmet was among the thousands of items deliberately collected during the James Cook expeditions (three voyages spanning 1768-1779). The second possible route is the George Vancouver excursions, where crew members also gathered ethnographic objects (1791-1795). Both of these itineraries would mean the mahiole traveled to Charleston by way of London. Charleston, even in the post-Revolutionary period, had strong trade and cultural connections with the British metropole.

The third very compelling possibility is an association with Boston. In a series of voyages to the Pacific between 1790 and 1793, a Boston sea captain by the name of Robert Gray became the first American to circumnavigate the globe. He is credited with being the first Euro-American in the Columbia River in Washington state, and opening the maritime fur trade. While noted primarily for his excursions in the Pacific Northwest, Gray also made a stop in Hawaii where he and crew members gathered a number of ethnographic objects including mahiole.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Which of these routes the object conclusively traveled is unclear. How “Major Ladson” acquired the object is even less clear. There are a few individuals by the surname of Ladson who served in the Revolutionary War; I believe it was most likely Major James Ladson who donated the helmet to the burgeoning museum. Ladson constructed a house on Meeting Street in Charleston in 1792 and served as Lieutenant Governor under William Moultrie from 1792 to 1794.

This initial iteration of what is today The Charleston Museum, then a component of The Library Society, burned shortly after its founding and began collecting again at the end of the eighteenth century. In the first accession book, currently housed at The Library Society, this “Indian helmet from the Sandwich Islands” is listed as one of the first acquired objects.

Although The Charleston Museum’s mahiole is special with its early accession date these objects are found in museums all over the world. For this research, I located mahiole in the collections of the British Museum (England), the Peabody Museum (Massachusetts), the Bishop Museum (Hawaii), and the Te Papa National Museum of New Zealand. Personally, I encountered a mahiole and ‘ahu ‘ula on display in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York) and Chief of Museum Operations Susan McKellar found one on exhibit at Musee d’ Aquitaine de Bordeaux, an object on loan from Musee d’Histoire Naturelle de Lille (France). The Charleston Museum is in good international company having one of these astounding objects in their collections, and the early date of its donation makes it all the more remarkable.

–Sarah Platt, PhD Candidate, Syracuse University