Shhh…It’s Wood Stork Nesting Season

For those of you who have had the good fortune to visit the wildlife pond at the Museum’s Dill Sanctuary, you may have had the opportunity to observe the wood storks that nest there in the spring and summer. Museum staff and volunteers are careful to avoid disturbing their activities especially during March to May as they are most sensitive during this egg laying period and prone to abandon nests if they perceive a threat.

The Dill Sanctuary’s six-acre wildlife pond is a unique resource and a tremendous asset to the property. When the property was bequeathed to the Museum in the 1980s by Pauline Dill, the last surviving Dill sister, sources of freshwater there were minimal, consisting primarily of a small irrigation pond used in farming operations prior to Museum acquisition. Ecological studies of the property suggested that additional water features would be necessary to attract greater bird populations, especially wading birds such as herons, ibises and wood storks. Fortunately, in 1994, Charleston County was undertaking a construction project which required a significant amount of fill. The Museum worked with County officials to construct a spring-fed wildlife pond at the Dill Sanctuary and the excavated soil was then used in the County project. Museum staff designed a layout for the pond which incorporated three islands, providing appropriate security for nests constructed on these islands. The pond, meanwhile, was made deep enough to discourage terrestrial predators such as bobcats, raccoons and opossum from easily accessing the islands. It was expected that alligators would also reside in the pond to further deter predators from the islands (this has, in fact, occurred). Wax myrtles, which grow quickly in the Lowcountry, were planted on the islands to provide wading bird nesting sites.

The installation of the pond has been an unquestioned success for the Dill Sanctuary, providing habitat for as many as 1,500 pairs of wading birds. Possibly most important of these are the wood storks. Due to habitat loss across the southeast, wood storks were declared an endangered species in 1984. Populations made a comeback in the succeeding three decades and were downlisted to “threatened” in 2014. Still, considering the continued growth of development in the Lowcountry, the species will need habitat such as that provided at the Dill Sanctuary to survive in our area.

To sustain their populations, wildlife biologists estimate that wood storks need to produce an average of 1.5 fledglings per nest. Typically nest building begins in late March/early April and lasts approximately one week. Eggs are then laid by the mother over a period of 5-7 days, which then take 28 days to incubate. Since the eggs are not all laid at once in the nest, hatching also occurs over several days with the last hatched birds being the least likely to survive. Parents feed their young small fish which they collect and bring to the nest throughout the day. When food is scarce, some of the young have difficulty surviving as a one-week old wood stork must compete for food with a two-week old sibling that is nearly twice its size. When food is abundant, however, the parents are able to provide enough sustenance to keep their entire brood of chicks alive. In addition to feeding their young, wood stork parents perform regular maintenance on the nests and protect their young from the summer heat by spreading their wings above them to shade them and by dribbling water collected in their beaks on them.

Fledging, in which the young wood storks grow their flight feathers and become strong enough to fly, takes 7-8 weeks from the time they hatch. They will take short flights at 7-8 weeks but do not depart from their colony until reaching 9-10 weeks.

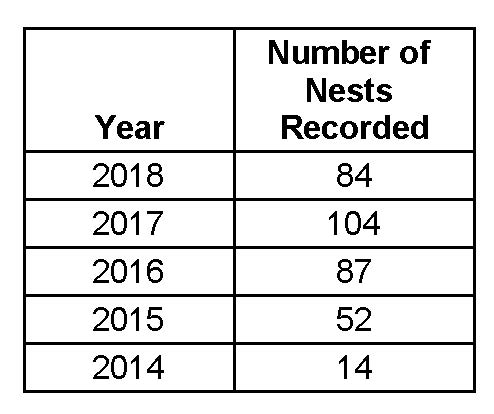

The South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (DNR) closely monitors wood stork nesting and populations across the state. Flying over in airplanes, DNR wildlife biologists have been able to determine the number of wood stork nests at the Dill Sanctuary for the last five years. The numbers they have observed are as follows:

Nesting at the Dill Sanctuary pond showed steady growth from 2014-2017, but declined in 2018. The winter storm of January 2018 which brought snow and ice to the Lowcountry may have contributed to this decrease as it damaged a number of the wax myrtle trees on the nesting islands. It will take another season to determine if the general upward trend will continue.

To further monitor the success of wood stork nesting at the Dill Sanctuary, beginning this nesting season, the Museum will be working with DNR to make the site an “index colony” for wood storks. DNR wildlife biologists will observe the wood storks from the ground throughout the season, taking careful measures to avoid any disturbance of the site. The data they collect will provide important information concerning the health of the population and the success of the Dill Sanctuary wood stork rookery. Like these biologists, if you see nesting wood storks, be sure to be very quiet and marvel at this remarkable species, which is making a comeback thanks to protected areas such as the Dill Sanctuary.

– Carl P. Borick, Director

Special thanks to Christy Hand, Wildlife Biologist with the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, for her assistance with this article.