Remnants of “Hessian” Fort Possibly Under Battery Pringle

Some years ago, on a trip to England, Larry Cadigan, a long-time volunteer in the Museum’s archaeology department, brought back a photocopy of an 18th century map he had identified that showed a “Hessian” redoubt on the Stono River on James Island. Ron Anthony, the Museum’s Archaeologist, suspected that the fortification on Cadigan’s map was probably in the same location of Battery Pringle. In 1995, the Museum contracted with the Army Corps of Engineers to install a rip rap barrier on the face of Battery Pringle to control erosion that was occurring due to regular tidal action. While the project was underway, Ron monitored the work to ensure that no archaeological features were disturbed. As the front of the battery was cleared on the Stono River side in preparation for the new rip rap barrier, he observed a distinct feature at the base of the battery which he surmised was an earlier Revolutionary War era fort.

Some years ago, on a trip to England, Larry Cadigan, a long-time volunteer in the Museum’s archaeology department, brought back a photocopy of an 18th century map he had identified that showed a “Hessian” redoubt on the Stono River on James Island. Ron Anthony, the Museum’s Archaeologist, suspected that the fortification on Cadigan’s map was probably in the same location of Battery Pringle. In 1995, the Museum contracted with the Army Corps of Engineers to install a rip rap barrier on the face of Battery Pringle to control erosion that was occurring due to regular tidal action. While the project was underway, Ron monitored the work to ensure that no archaeological features were disturbed. As the front of the battery was cleared on the Stono River side in preparation for the new rip rap barrier, he observed a distinct feature at the base of the battery which he surmised was an earlier Revolutionary War era fort.

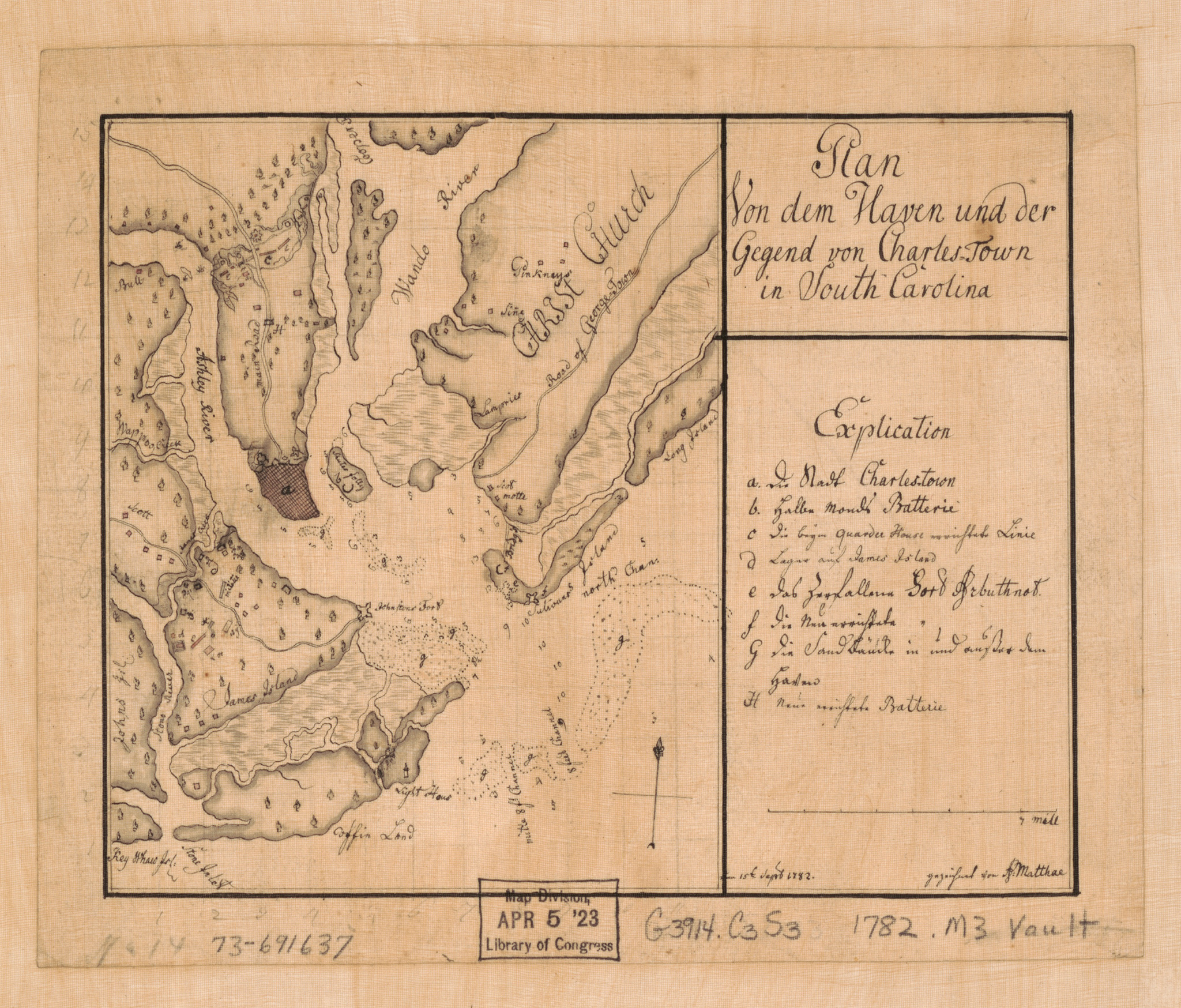

Beginning in 1995, the Library of Congress began a digitization project to make more of their holdings available online, and over time an increasing number of photographs and historic images have become accessible. Among them is a version of the map that Larry Cadigan had originally located in England. The map, entitled Plan von dem Haven und der gegen von Charles-Town in South Carolina in German, translates to plan of the harbor in the area of Charles-Town It shows British fortifications around Charleston in 1782 and there is a distinct redoubt south of Newtown Cut (James Creek on the map) and north of the bend in the river.

Although its location is conjectural based on the map’s somewhat imprecise scale, the strategic points on the Stono River did not change between the Revolutionary War and the Civil War. The site of Battery Pringle offers a field of fire down the Stono that kept Union ships from making their way upriver to outflank Confederate defenses. A British or Hessian battery during the Revolution would have been intended to do the same. Based on this map and the feature witnessed by Ron, it would appear that this may be the “missing” Hessian redoubt.

The map has added to our understanding of the Revolutionary War history of the Dill Sanctuary. Based on earlier research, we knew that there was significant activity on the property during 1780, when British and Hessian troops encamped at what was then Paul Hamilton’s plantation prior to the Siege of Charleston. We now know that there was subsequent occupation by Crown troops and an important fortification on the Stono that protected their rear. Future archaeology may shed further light on this history.

Hessian troops, such as the Regiment von Dittfurth, comprised much of Charleston’s garrison during the British occupation.

Prints, Drawings and Watercolors from the Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Brown Digital Repository, Brown University Library

Who were these Hessians and why were they on James Island? At the outset of the rebellion in America, realizing that their regular military establishment was too small to conquer the colonies, the British Crown contracted with several of the leaders of the German principalities to hire out troops for service in America. These men came from places such as Brunswick, Anspach-Bayreuth, Waldeck and Hesse-Hanau. The largest contingent came from Hesse Cassel, however, and as a result these men were universally referred to as Hessians. They were good, professional soldiers and often performed expertly for the British in battles such as that at Long Island and Fort Washington in 1776. At Trenton, the battle most people are familiar with, where Hessian troops suffered their worst defeat, they were unsupported by other British forces and completely overwhelmed in numbers by Washington’s army. They made up a significant portion of the army that besieged Charleston in 1780 and comprised a sizable part of the garrison that occupied the city until December 1782. James Island protected the southwest approach to Charleston so the British strengthened Fort Johnson and built additional fortifications across the island, including the redoubt on the Stono. These defenses were often manned by Hessian soldiers.

Because America contained a large number of German settlers, Hessian troops melded reasonably well with the local populace. This created problems for their officers as desertions were frequent. In one case, such a desire to leave the service and settle in Charleston came from an officer, Lewis Wernicke. Wernicke, second lieutenant in the Regiment d’Angelleli, the same regiment that had been decimated at Trenton, submitted his resignation in the fall of 1781 as he wished to marry a local widow named Ann Bishop. According to his commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Johann Endmann, Wernicke had become involved with a woman of questionable character. He reported to his Landgrave in Germany on November 11, 1781 that she had already had two husbands, “has a very bad reputation,” and was “far advanced in pregnancy.” Before the resignation could be accepted, however, Wernicke married Bishop as reported in the December 1, 1781 Royal South Carolina Gazette. Endmann wrote the Landgrave shortly thereafter that “the discovery of his marriage with this female of very bad reputation would have made it necessary…to have him discharged in any case.” So much for keeping up the standards of the Hessian officer corps. Despite the objections of his superiors, we can only presume that Mr. and Mrs. Lewis Wernicke lived happily ever after.