Pottery, Archaeology & the Catawba Nation

The Catawba Nation in present-day Rock Hill is South Carolina’s only federally recognized tribe. Today, Catawba artisans are nationally recognized for their skill in producing highly burnished pottery, described by ethnohistorian Thomas Blumer as “a cultural treasure of tremendous worth.” The Museum’s collection features artisan vessels and archaeological fragments.

During the early colonial period, the Esaw gave rise to the Catawba nation by asimilating smaller nations to form a confederation. After the Yamasee War of 1715, the Catawba received privileged trading status from Carolina’s colonial government. King Hagler (Nopkehe) led the Catawba from 1754 to 1763. Catawba men returning from battle in the Seven Years War (1757-1763) brought smallpox to the nation, and nearly half the population was lost. Survivors fled to their ancestral territory, Cofitachequi, at Pine Tree Hill, or Camden, where they remained for two years. Following the American Revolution, the newly-constituted State of South Carolina recognized the 1763 Catawba reservation lands near Rock Hill.

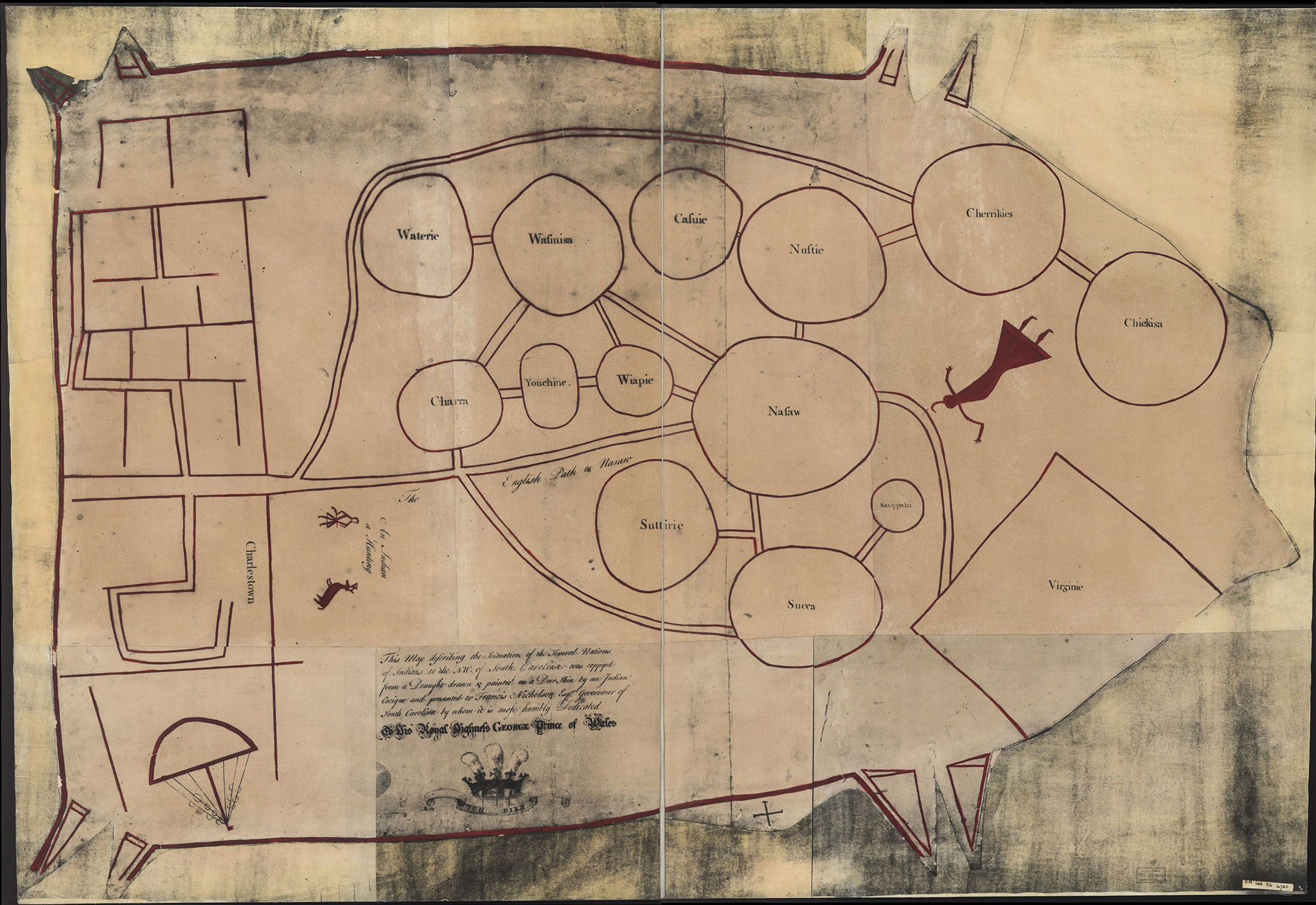

The 1721 “Map of Several Nations” presented to Governor Francis Nicholson shows the Catawba (Nassaw) as the hub that linked Charles Town and Virginia to other tribes (Library of Congress).

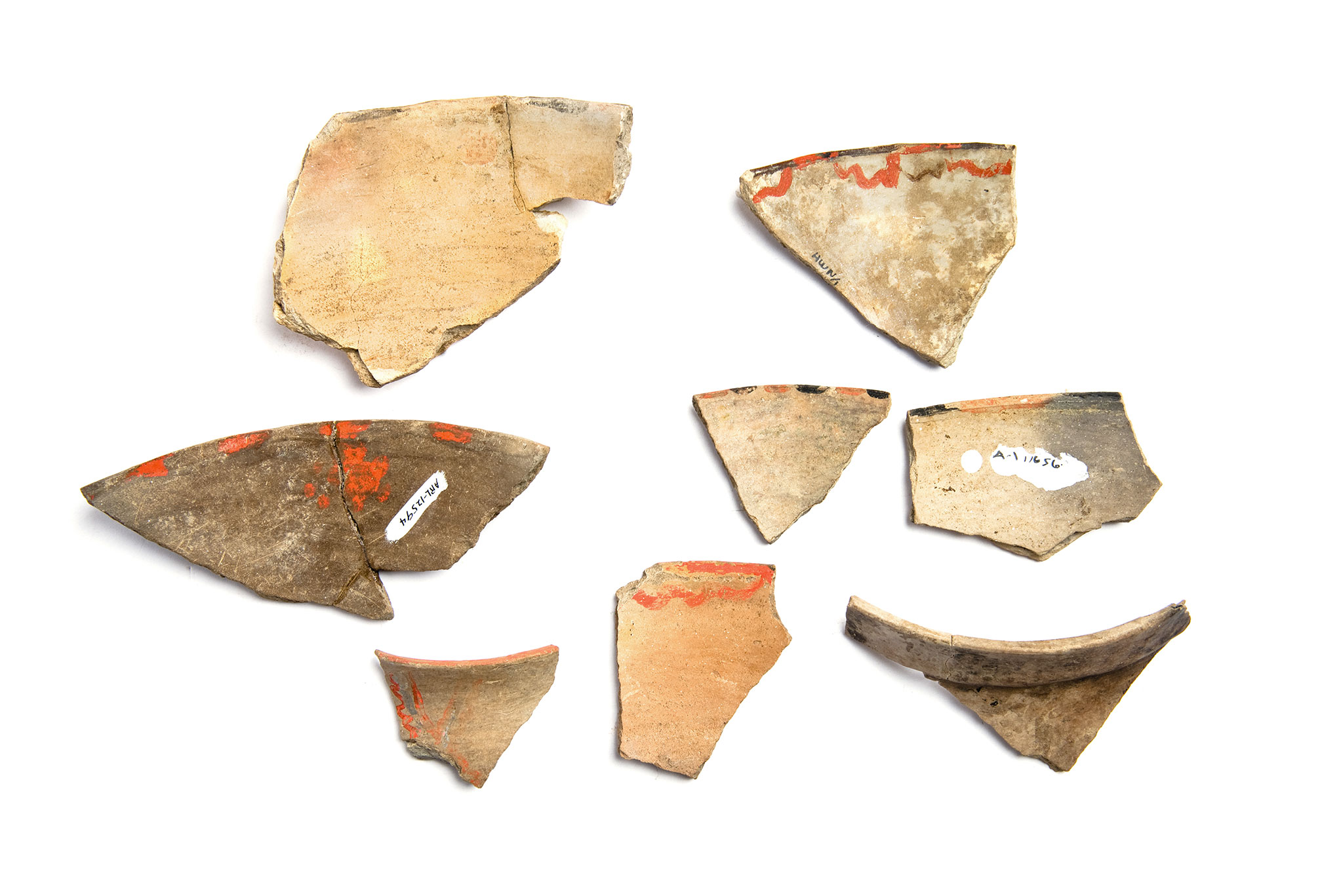

Archaeological examples of Catawba pottery recovered from sites in Charleston, late 18th to early 19th century. The fragments are distinguished by a smooth, hard finish and flecks of mica. Many are decorated with red and black paint.

The Catawba revised their pottery tradition after their return to the Catawba River reservation. Stamped pottery common to Native peoples throughout the southeast was replaced with a homogenous, highly burnished style. The potters experienced a commercial demand for earthenware, and so reoriented their production to meet the market. Catawba women assumed new, and eventually dominant, roles in the nation’s economy.

Moreover, many Catawba became itinerant merchants, moving from the piedmont to the coast, where women made pottery and men hunted game. Santee River plantation owner Philip Porcher recalled that “the Catawba Indians….traveled down from the upcountry to Charleston, making clay along the way. They would camp until a section was supplied, then move on, till finally Charleston was reached” (Simms 1852).

A nearly-complete Catawba ware pitcher, decorated in red and black floral design, was recovered from a privy at 107 Church Street in the 1970s.

Archaeologists long suspected some of the more refined colonoware fragments from 19th century contexts were the product of Catawba potters. Then, beginning in 2004 archaeologists at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill discovered the sites of Old Town, Ayers Town, and New Town. These sites, occupied from the late 18th to early 19th century, produced clear evidence of market-level pottery production. Moreover, many of the fragments recovered in Charleston matched those found at the Catawba towns.

Many of our archaeological examples have distinctive painted decoration in red/orange and black. We find open bowls, often with faceted rims, jars, and even pitchers. A mostly complete pitcher came from 107 Church Street, and the Heyward Washington house produced numerous examples, mostly from the kitchen cellar.

A small pot made by Foxx Ayers, 1986. Foxx and his wife, Sarah, were well-known Catawba potters, and frequent guests at archaeology gatherings.

A vase made for The Charleston Museum by Martha Harris Sanders in 1964

The Museum’s history collection includes a handled vase dating to the mid-19th century that belonged to Samuel Cordes of Yaughan plantation in Berkeley County. (Archaeological excavations at Yaughan Plantation in the 1970s were among the first to produce colonowares.) The black burnished vessel has traces of red paint around the rim and is the oldest complete example in our collection. We also house an important collection of vessels from the early to mid-20th century that will be displayed in our postbellum section to illustrate the resilience of the Catawba people and the current place of this sovereign nation in our state.

These archaeological and historical examples of Catawba pottery demonstrate the integral role of the Catawba Nation in the history of South Carolina. The Catawba produced pottery continuously to the present day, and it remains central to their individual and collective identity.

This pitcher, purchased by Dr. Samuel Cordes of Yaughan Plantation, Berkeley County, is the oldest in the Museum’s history collection. There are faint traces of red paint around the rim. Originally dated to 1805, recent examination by David Cranford, Brent Burgin, and Brooke Bauer suggests a mid-19th century date, and possibly production by Billy George.

For further reading see: