Martha Zierden on “Charleston: An Archaeology of Life in a Coastal Community,” written by herself and Elizabeth Reitz

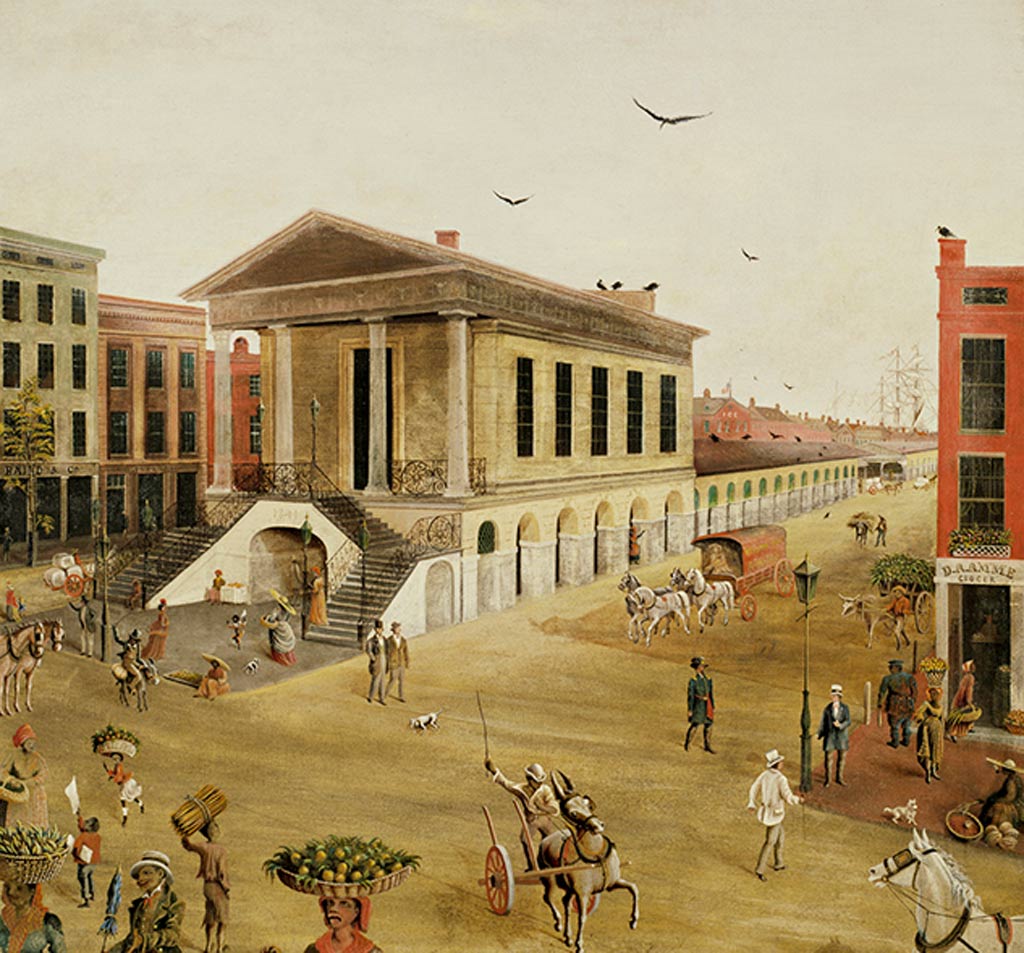

I have the good fortune of studying one of America’s most historic cities for over thirty years, doing so by digging in the ground and recovering archaeological evidence. Charleston is well-known as the birthplace of the historic preservation movement, but, for the most part, is not widely known as a world-class archaeological site. Yet it is this aspect of the city’s physical and social world that speaks to daily life in the historic city, for everyone who lived and worked here, not just the wealthy and literate.

The Charleston Museum’s pioneering research in urban archaeology began with Dr. Elaine Herold in 1974, and continued with my arrival in 1981. It was already apparent that Charleston sites produce a huge quantity and variety of artifacts, and many of these were well preserved. Among them were faunal remains, bones from animals that lived and died in the city, those that fed the city’s residents. Knowing that faunal analysis could be informative, I began collaborating with Dr. Elizabeth Reitz, a new professor at the University of Georgia. Soon, some of the most interesting new information was coming from the faunal analysis.

We realized that a book on Charleston archaeology was in order, but years passed before we found the time to put it together. By then, we almost had too much to say. We decided to tell the story of Charleston through the lens of animal use and diet. We all love to eat and Charleston has become a food destination. Moreover, animals were part of the city’s landscape well into the twentieth century, living in the back yards of most houses.

Charleston takes the reader on an archaeological tour of the city. We describe the projects, highlighting the fun and exciting aspects of fieldwork, from digging in the basement of City Hall to opening a giant hole at South Adger’s Wharf to find the city wall. There are images of some of the most interesting and unusual artifacts that have been recovered from the deep soil layers. We use the evidence from animal bones (134,000 of them) and other artifacts to describe the city’s foodways and diet from the late 17th century to the late 19th century.

The coast of Charleston was bountiful. Charlestonians used cattle and pigs, as well as their flocks of chickens, pigeons, and ducks as a basis for their diet. Cattle, in particular, flourished in the pine forests and swamps of the lowcountry, and early colonists took advantage of this environmental setting. City dwellers also drew from the resources of the surrounding coast to expand and enliven their meals. Freshwater and marine fishes were commonly eaten, as were Canada geese, turkeys, alligators, and turtles. We have a composite signature of a vibrant, densely packed city, where people and animals lived in close proximity. Archaeology provides only a partial picture of city life, but it provides one that differs from our traditional view of Charleston’s history.