Charleston’s Porgy and Bess

Published in 1925, Porgy, the woeful tale of an African American beggar and his relationships with Bess and others who lived in the “Row” come directly from the observations and experiences Du Bose Heyward encountered while growing up in the economically depressed Charleston of the early 1900s. Frequently ill as a child, Heyward spent much of his time bedridden. Influenced in a large part by his mother, he used this time to study literature and honed his writing skills by composing poetry and short essays.

Photograph of Du Bose Heyward sitting next to Mary P. Means as they ride the Folly Beach ferry, c.1920

Photograph of Du Bose Heyward sitting next to Mary P. Means as they ride the Folly Beach ferry, c.1920

Although, descended from one of Charleston’s aristocratic families, Heyward did not grow up in a luxurious setting. He was just two years old when his father, Edwin, died forcing his mother, Janie, to work odd jobs which she supplemented by writing poetry to meet expenses. The young Du Bose sold newspapers until he dropped out of school at age fourteen to work in a hardware store. He later worked among the black stevedores as a steamship checker and by twenty-three was an insurance agent at R.M. Marshall & Brothers on Broad Street. Heyward soon after partnered with childhood friend, Harry J. O’Neill, and together they created the Heyward & O’Neill insurance company. At last financially independent, Heyward moved into a house at 76 Church Street (now the Du Bose Heyward House) and in 1922 won a fellowship at the MacDowell Colony in New Hampshire for writers, poets, playwrights, artists and composers. There he met his wife, Dorothy, a playwright, and moved back to Charleston.

Photograph of a young passenger in his goat cart in the early 1900s taken by Helen Walker Tucker

Photograph of a young passenger in his goat cart in the early 1900s taken by Helen Walker Tucker

Two days later, Porgy drove his chariot out through the wide entrance into a land of romance and adventure. He was seated with the utmost gravity in an inverted packing-case that proclaimed with unconscious irony the virtues of a well-known toilet soap. Beneath the box two solid lop-sided wheels turned heavily. Before him, between a pair of improvised shafts, a patriarchal goat tugged with the dogged persistence of age which has been placed upon its mettle, and flaunted an intolerable stench in the face of the complaisant and virtuous soap box.

The character “Porgy” in Du Bose Heyward’s novel of the same name was inspired from a man known in Charleston as Samuel “Goat Cart Sam” Smalls, a crippled black man who sold peanuts and used a goat-drawn cart as his mode of transportation. Unlike Heyward’s Porgy, however, Samuel Smalls was known as a rather cruel and unkind man with a propensity for drink according to acquaintances who interacted with him in the African American community. He apparently was somewhat of a ladies’ man and heavy gambler who could be found often at a popular gambling spot called the Bull Pen on Charleston’s Neck where his goat would wait patiently outside. One particular News and Courier crime report details an incident in which Smalls attempted to escape the police in his goat cart after he shot at a woman named Maggie Barnes. Heyward read about the mad dash for freedom and was apparently impressed enough with Smalls’s daring that he recreated the scene for Porgy in a more heroic light.

Photograph of Cabbage Row in 1928 taken by John Bennett

Photograph of Cabbage Row in 1928 taken by John Bennett

Catfish Row, in which Porgy lived, was not a row at all, but a great brick structure that lifted its three stories about the three sides of a court. The fourth side was partly closed by a high wall, surmounted by jagged edges of broken glass set firmly in old lime plaster, and pierced in its center by a wide entrance-way.

The famous Catfish Row that Heyward immortalized in his novel is known more commonly as Cabbage Row in Charleston. Located at 89-91 Church Street, the “Row” is actually a pair of three-story buildings connected by a central arcade that leads to an inner courtyard. During the time that Du Bose and Dorothy lived in their Church Street home, African Americans inhabited these decaying structures, residing on the top two floors while using the ground floor to sell cabbage and a variety of other vegetables from the front windows. It is no wonder then why Heyward chose this setting as the focal point for his characters to live and gather after a long day’s work of loading cotton and cleaning mansions. Passing the tenements everyday on the way to his office on Broad Street, Heyward would have no doubt witnessed the lively interactions between the people living in the “Row’s court.”

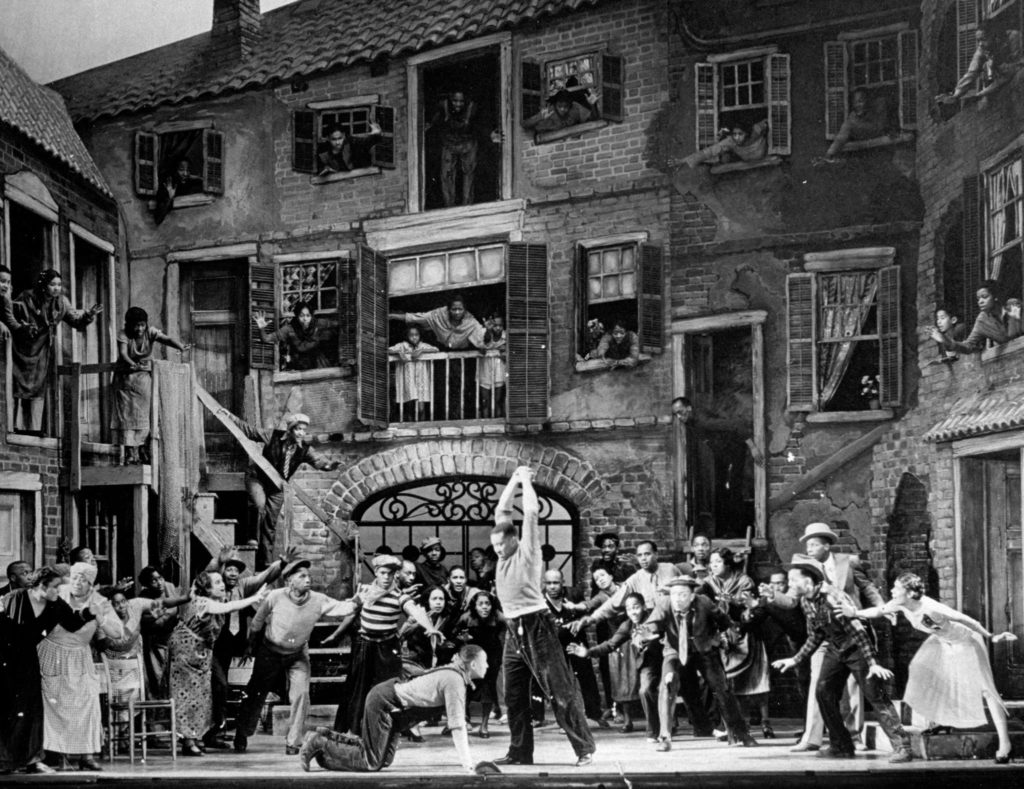

Porgy and Bess, Act 1 Scene 1 performed at the Colonial Theatre in Boston, September 1935

Porgy and Bess, Act 1 Scene 1 performed at the Colonial Theatre in Boston, September 1935

The end came quickly, and with startling suddenness. Crown broke his adversary’s weakening hold, and held him the length of one mighty arm. The other swung the cotton-hook downward. Then he dropped his victim, and swaggered drunkenly toward the street. Even to the most inexperienced the result would have been obvious. Robbins was dead: horribly dead.

Though Heyward’s Porgy was well received after its publication, Porgy, Bess, Maria, Crown and Sportin’ Life did not gain legendary fame until George Gershwin read the entire novel one sleepless night. Immediately writing to Heyward, he proposed turning his story into an opera. Dorothy had begun to transform the book into a play, however, and recalled later that Gershwin seemed not to mind postponing his plans. She wrote, “it was a great moment when George said there was plenty of room for both play and opera. And plenty of time. He wanted to spend years in study before composing his opera.” Gershwin would go on to write three satirical operettas while Dorothy and Du Bose finished their play. Premiering on October 10, 1927 as Porgy: A Play in Four Acts at the Guild Theatre in New York City, it featured an all African American cast and ran until August of 1928.

Finally in 1933, Gershwin and Heyward began work on Porgy and Bess. Du Bose with the help of Ira Gershwin converted the novel into an opera libretto while George composed its music. Spending some time on Folly Beach and attending more than one “Negro spiritual,” Gershwin composed the music over an eleven month span and then took another nine months to orchestrate it. Two years later, on September 20, 1935, Porgy and Bess premiered at the Colonial Theatre in Boston before making its New York debut at the Alvin Theatre on October 10, 1935.

Incredibly, after two attempts to desegregate the Dock Street Theatre, the opera would not be performed in Charleston until 1970. The first attempt was in 1935 when the all black cast refused to perform in front of a segregated audience. The second attempt in 1954 gained a little more attention with four shows scheduled, but only after a compromise had been reached to seat blacks on one side of the auditorium and whites on the other. Unfortunately, after receiving both local and national pressure concerning the integrated seating, the theatre shut down the production with several rehearsals as the only evidence the show was ever in Charleston.