Bringing Them Back to Life: The Pelagornis

Bringing Them Back to Life is a blog series from The Charleston Museum that provides updates and plans for our Natural History Gallery renovations.

First, a big thank you to all those who have responded to our fundraising mailing and made a donation to the Natural History Gallery project. Your gifts have moved us closer to our goal and we are most grateful! If you have not and would like to make a contribution, please send your gift using the mailer card that was sent to you or visit our website to donate by credit card: https://www.charlestonmuseum.org/support-us/donate/ (click the Natural History Gallery button). We so appreciate your support of this critical project.

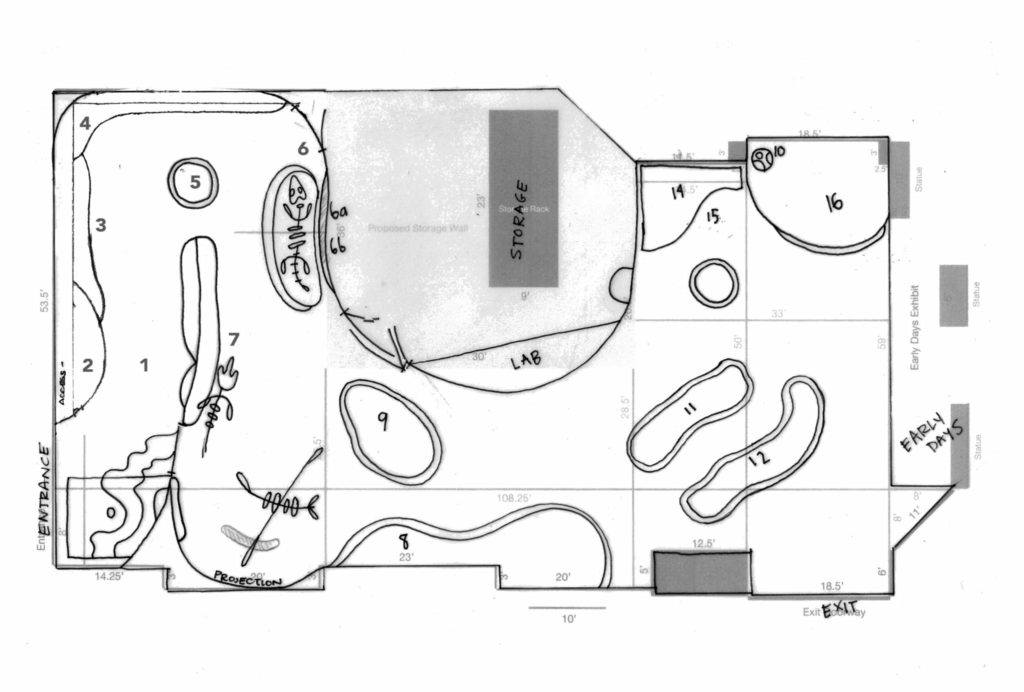

Much effort is going into the Natural History Gallery planning process. Curator of Natural History Matt Gibson has been deeply involved since the outset formulating concepts for the gallery, developing an initial floor plan, selecting and researching fossils and specimens, and writing interpretive labels for display panels. Becca Barnet, of Sisal & Tow, our designer for the project, has come up with a splendid design concept based on Matt’s initial plan.

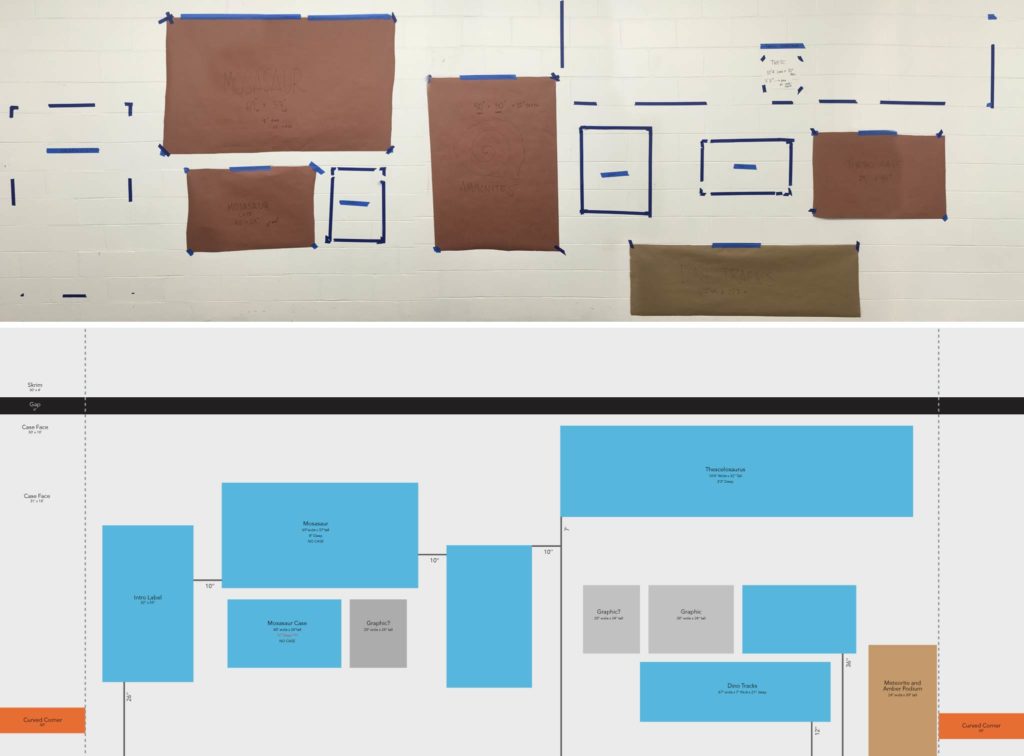

We are now in the process of further refining this design by looking more closely at the individual components that will comprise the gallery. Matt, Becca, and Sean Money, the Museum’s staff Graphic Designer, are going through the preliminary gallery design section by section to determine the specifics of each. How does this happen? After Matt has identified the elements that will appear in each area, the team then maps out the number and size of large casts, exhibit cases, explanatory panels and graphics using blue tape on a wall that has dimensions that exactly match the exhibit section. Based on photographs of this layout, Sean and Becca then use a design program to give this more substance. Becca can then use these details in creating a final layout with specific dimensions. It is a complex but fulfilling task for the team. They will continue this process until all sections are complete, and we anticipate having a final design plan by September, just one year out from our planned opening for the gallery.

More details are yet to come, but in the meantime, please enjoy Matt’s piece on the Pelagornis sandersi, the world’s largest ever known flying bird and one of the key exhibits in the new gallery.

The Pelagornis

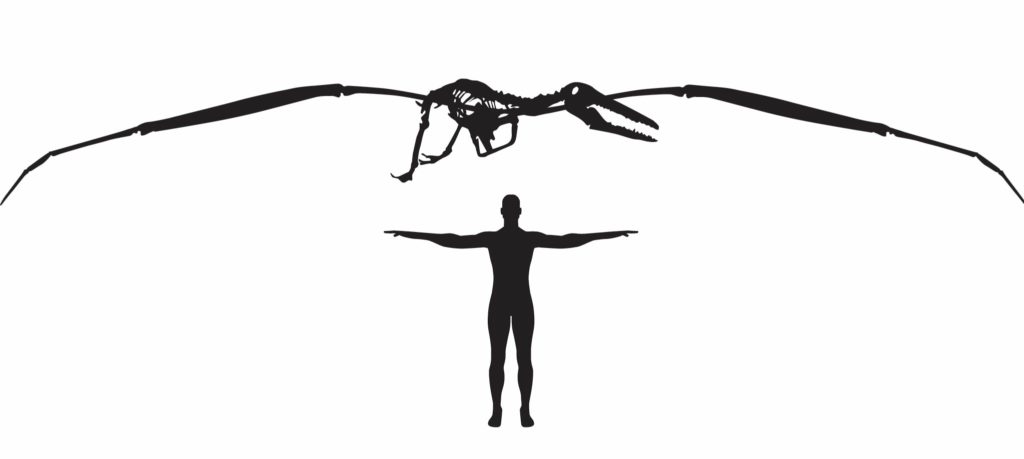

The largest ever known flying bird, Pelagornis sandersi, is currently on display in The Charleston Museum’s Natural History Gallery, but will have a special section dedicated to it in the new gallery. This specimen was excavated at the Charleston International Airport by Museum staff and volunteers in 1983 and was formally described in 2014. The exhibit will cover its excavation, preparation, and interpretation and will contain an interactive component that will deal with how such a large bird, weighing 50-80 lbs., could have taken flight.

Pelagornis belongs to a group of birds known as pseudodontorns, or false-toothed birds, so named because of the bony projections which grew from their beaks. Although they appear to be teeth and serve the same function, they are not true teeth. This means if Pelagornis lost a “tooth” it was actually breaking off a piece of its jaw. These “teeth” would have helped the bird snag fish and other marine creatures off the surface of the ocean.

Pseudodontorns are extinct relatives of water fowl such as pelicans and albatrosses and roamed the skies during the early Eocene, about 50 million years ago. P. sandersi, specifically, lived during the Oligocene roughly 28 million years ago. With a wingspan of 20 – 24 feet, P. sandersi, in addition to flapping its wings, utilized ocean wind currents to glide over long distances. With its enormous wingspan, this specimen exceeds the previous maximum wingspan for active “flapping flight.” Although there are some extinct animals larger than Pelagornis, like pterosaurs, they would have relied almost entirely on gliding. The new exhibit will go into greater detail on how Pelagornis flew and how this magnificent specimen is changing what we know about the physics of bird flight.