Archaeology and the Siege of Charleston

By Carl P. Borick, Director

Based on documentary sources such as period maps and firsthand descriptions, we have a fairly solid estimation of where the American defenses and British parallels were located during the Revolutionary War Siege of Charleston in 1780. The American defenses consisted of a line of redoubts and batteries connected by a parapet which stretched across the peninsula from the Cooper River to the marshes which then existed just west of Smith Street (the reason for so much flooding in the MUSC area during heavy rains and high tides). In front of this line, which bristled with over 200 cannon, engineers created a canal, or moat, which ran from a large tidal creek on the Cooper River and ended in the environs of modern Pitt and Duncan Streets. The Americans built a dam on the tidal creek, which most likely employed the same type of technology as used in canal gates on rice plantations. When the tide was coming in, the gates were opened; when it was going out, they were closed to keep water in and the moat full.

Remnant of tabby curtain wall of Revolutionary War Hornwork in Marion Square.

Behind the main defense line stood the substantial Hornwork, made of rock-solid tabby. A “hornwork” is defined as two bastions connected by a curtain wall. During the siege, American soldiers completely enclosed it by adding a rear wall, which was probably earthen rather than tabby. The Hornwork served as a command post for Major General Benjamin Lincoln, the commander of American forces in the South, and was to be an “Alamo” of sorts, where soldiers were to retreat to, if the British breached the main defense line. The tabby remnant in Marion Square, a piece of the curtain wall which connected the Hornwork’s two large bastions, is one of only two immediately apparent physical reminders of the Siege of Charleston that can be seen in the City today. The other is the broken right arm of the statue of William Pitt in the Charleston County Judicial Center. Pitt, a member of the British Parliament, was a hero to Americans for his support of their rights during the Stamp Act crisis; ironically, a British cannon ball, fired from James Island, smashed the right arm of the statue during the Siege.

Where are the other remnants you might ask? Documentary sources have provided answers to siege locations but what about archaeology? What has been the Museum’s involvement in this research? Archaeology has been somewhat inconclusive regarding the exact locations of the siege works. The footprint of the right bastion of the Hornwork was revealed in narrow trenches excavated by New South Associates in a 1998 project, but no archaeological evidence of the main American defense line or the British siege parallels has ever been found, however.

Archaeology has provided a few tantalizing artifacts related to the Siege. Among them are a piece of grapeshot, a four pound cannon ball and an unexploded shell. The grapeshot came from the rear yard of the Aiken Rhett House during a Museum led archaeological dig in the late 1990s. Found in the probable environs of the British third parallel, this anti-personnel projectile was most likely fired at the besieging forces from the American defenses just a few hundred yards to the south. The four pound cannon ball was found by archaeologist Carl Steen under a house on Vanderhorst Street, which is just south of the approximate site of the west end of the American defense line. Construction crews uncovered the shell during the renovation of the Gaillard Center, an area that would have been just south of the American lines, so a definite overshot by British artillerymen. The grape shot and cannon ball are in the Museum’s collections while the shell belongs to the City of Charleston.

Jon Marcoux performing magnetic gradiometry at Wragg Square. This method identifies buried archaeological features by measuring magnetic fields below the surface.

Attempts have been made to find other archaeological evidence but these have revealed little. In 2012, based on information provided by Martha Zierden, the Museum’s Curator of Historical Archaeology, and me, Dr. Jon Marcoux surveyed both Wragg Mall and Wragg Square using magnetic gradiometry. The magnetic gradiometer identifies buried archaeological features by measuring magnetic fields below the surface of the site. Based on period maps and current elevations, clearly part of the American defense line ran through present day Wragg Square, bordered by Ashmead Place, Meeting Street and Charlotte Street. Period maps seem to indicate, meanwhile, that part of the British third parallel may have crossed part of Wragg Mall, just north of the Museum. At the same time Marcoux did his testing, Brockington and Associates attempted limited ground penetrating radar at Wragg Mall. Both were inconclusive. Interference from buried water and electric lines probably prevented identification by the magnetometry and the ground penetrating radar covered only a small geographic area. An earlier limited survey by Zierden during installation of a new fountain in Wragg Mall also yielded little.

City-sponsored construction project at Wragg Square, which was monitored by Museum archaeologists Martha Zierden and Ron Anthony.

City-sponsored construction project at Wragg Square, which was monitored by Museum archaeologists Martha Zierden and Ron Anthony.

In 2015, the City of Charleston put forth plans for updates to Wragg Square and Museum staff were invited to attend stakeholder meetings. Zierden suggested that the Museum could perform archaeological monitoring of any digging related to construction and City staff welcomed this idea. The first major step in the renovation process was replacement of the stairs leading from Meeting Street into the park. This promised to provide an excellent opportunity to view a profile of this “ridge,” where part of the defense line seems to have been located. During a cold, rainy week in January 2016, a construction crew broke up the old steps and part of the associated brick wall, exposing significant soil below the present ground surface. Zierden and Museum Archaeologist Ron Anthony monitored the work.

Note dark band of soil extending downward in center. The dotted line beneath it runs along what may be the base of a man-made feature, possibly the slope of a ditch related to the Siege.

The excavated area consisted of two trenches running east/west, on either side of the new stair foundation. The south profile immediately demonstrated that the elevation of Wragg Square is entirely natural, and not the product of fill. The north profile was completely different. Here was a large pit, or trench, that sloped from west to east. There were six bands of fill, including a distinct band of dark soil. There were no artifacts in the soil layers, hampering dating of the impressive soil feature. Overall the artifacts were very sparse, as would be expected on a site without any domestic occupation (Wragg Square was established in 1801 and was uninhabited prior to that time). Although an apparent feature was discovered, identification of what it represented could not be formally ascertained without further investigation, which was not possible due to the completion of the stairs project.

The Museum also conducted testing in the basement of the Joseph Manigault House in 2015 as part of the College of Charleston’s biannual Field School. Located between the Museum and Wragg Square, so just north of the American defenses, the possibility existed for some finds related to the Siege. Zierden and her team were disappointed to find that not only was there no evidence related to 1780, there was little even connected to the early nineteenth century occupation of the house. Much of the basement fill was evidently removed in the early twentieth century.

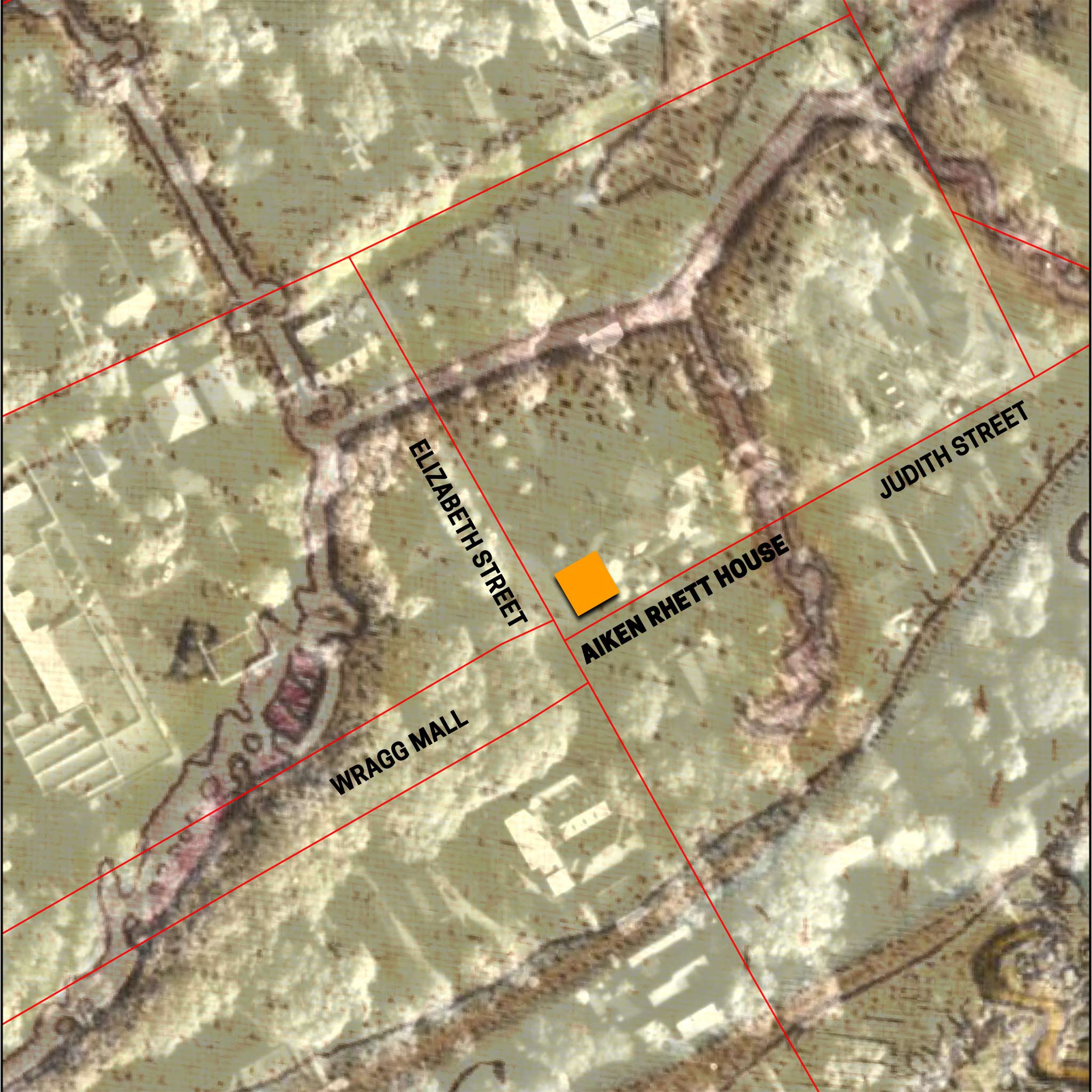

Detail from Charles Blaskowitz’s map of the Siege of Charleston showing approximate location of the Historic Charleston Foundation’s Aiken Rhett House in relation to a section of the British third parallel. Image courtesy of Jon Marcoux.

To date, then, attempts to identify features related to the Siege of Charleston archaeologically have come up empty. That may change this summer, however. In May-June, the Museum is again partnering with the College of Charleston for the Field School. Among the places that instructors and students will dig is the rear yard of the Aiken Rhett House. More recent work by Dr. Marcoux with ground penetrating radar has defined a large linear feature in the yard. Examination of a detail from a map created by Charles Blaskowitz, a British officer who drew the definitive map of the Siege, provides evidence that the British third parallel crossed through here. Moreover, ground topography just to the north on Mary Street seems to match the presence of eighteenth century tidal creeks in the area. Although they have met dead ends before, Museum and Historic Charleston Foundation staff are cautiously optimistic about the presence of the British parallel in the Aiken Rhett yard. It will remain to be seen what, if anything, can be discovered. Until that time, direct evidence of the Siege in downtown Charleston will remain a piece of tabby, an armless statute and a few projectiles.

If you want to learn more about the Siege of Charleston and where it took place in downtown Charleston, join us for Director Carl Borick’s siege lines tour on May 11.