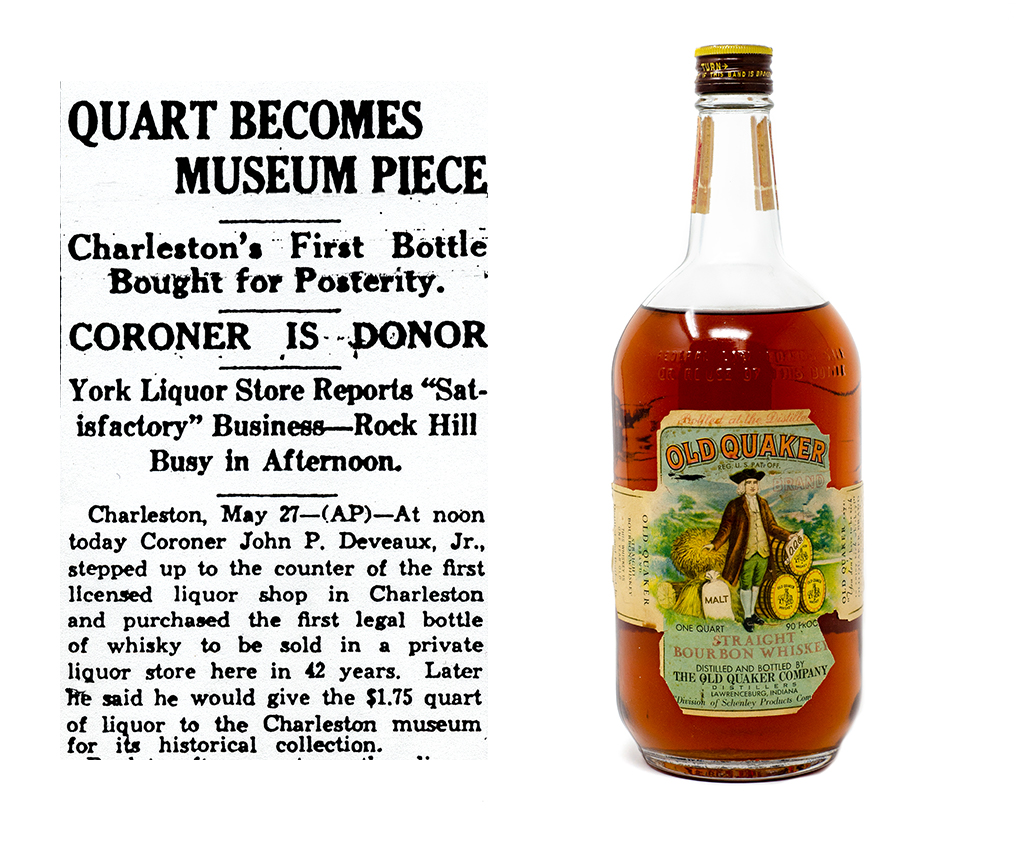

A Bottle of Old Quaker for Posterity

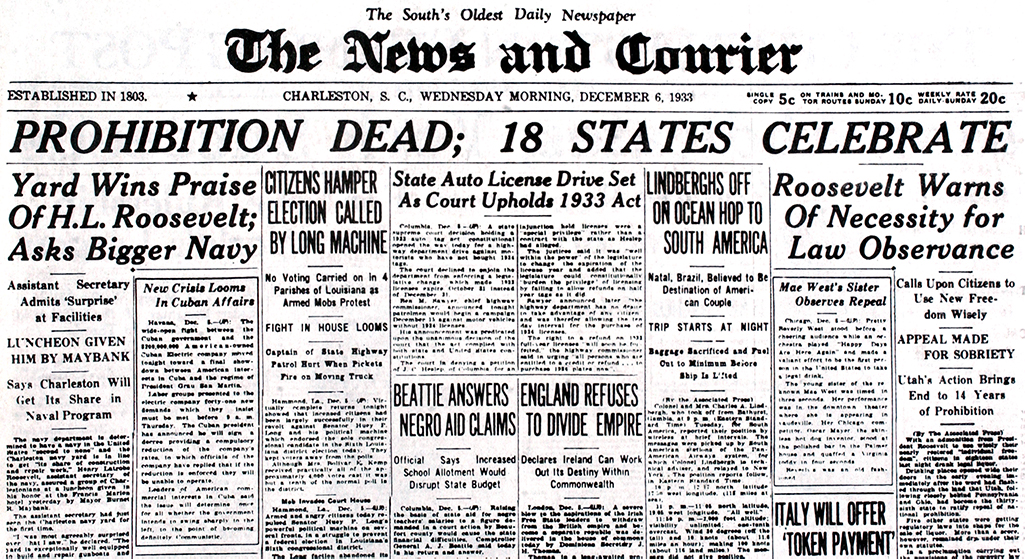

In its headline, with one-inch-tall letters, The News and Courier declared “Prohibition Dead” on December 6, 1933. However, it was not as if locals here were high and dry one day, then popping champagne corks the next. Despite the thirty-six states who ratified the 21st Amendment, South Carolina wasn’t one of them. For anti-prohibitionists, the national law that had outlawed the “manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors” in the U.S. would die a much belated, agonizingly slow death in South Carolina.

It’s important to note that the federal repeal of prohibition did not necessarily grant every citizen everywhere the right to drink up. Rather, it returned the whole issue back to the individual states, who could now decide one of two things: keep the state dry in its entirety, or exercise a “local option” and pass the decision down to counties, cities, and towns.

Whether or not to stay “wet” or “dry” was an issue Charleston and the rest of the state had been dealing with as far back as 1829, upon the founding of its first statewide temperance society. A decade later, its membership had increased to the point where they could no longer be overlooked by state legislators. By 1847, the national Sons of Temperance had set up its South Carolina Division and, together with plenty of other local, like-minded societies, had the governor’s ear.

Within two years, State law had made illegal all purchases of liquor in anything less than a one-quart containers and any “on-site” consumption of it was a jailable offense. For local teetotalers, it was a decent first step but nowhere near their ultimate goal. Though the Civil War and its fallout put most temperance efforts in South Carolina on hold, its stern messages were being circulated once again in the 1870s, this time louder and more vehement than ever before. In 1889, citing alcohol in all its forms as “the cause of most crimes and much poverty,” lawmakers brought forth a bill calling for the complete, statewide prohibition of all alcoholic beverages. It failed, but only by eight votes.

The state, poised to have another go at it, this time was thwarted by Governor “Pitchfork” Benjamin R. Tillman, who stepped in 1892 with a rather unorthodox idea. Proposing a “dispensary system” modeled after those in Europe, Tillman attempted to appease both sides of the temperance issue with a policy of strict government control over all movement and sales of alcoholic beverages. A state board was set up to regulate pricing, appoint local distributors, and, most importantly, divide profits made from the sale of alcohol equally between the state, its counties, and cities. South Carolina was the only state ever to establish such an enterprise – and it was a disaster almost from the start.

Viewed by most as a government monopoly, The State newspaper denounced the movement as the “czarism of Tillman.” Private wholesalers, brewers, and distillers lost their livelihoods. Worse, whatever funds were supposed to be distributed among municipalities were almost nonexistent. Public schools, for example, only received about one-tenth of the dispensary-generated cash that had been promised them. In 1907, the South Carolina Dispensary system, fraught with corruption, was justifiably closed down. Stopping short of going cold turkey, though, the state legislature allowed individual counties to decide whether to continue with their own dispensaries rather than embrace prohibition. A few did and, to their credit, did so successfully.

Nevertheless, pointing to the failed dispensary as even more proof of alcohol’s ills, a referendum put statewide prohibition to the vote in 1915. It passed by a two-thirds margin, and South Carolina, collectively, dried up on New Year’s Day 1916 – four years before the rest of the nation would ratify the 18th Amendment and illegalize all its booze.

Of the many planks in Franklin D. Roosevelt’s platform during his first presidential campaign of 1932, one that certainly did not go unnoticed was his promise to repeal national prohibition. Proclaiming eight days after his inauguration, “I think this would be a good time for beer,” President Roosevelt signed the Cullen–Harrison Act (or the Beer and Wine Revenue Act) which legalized and, of course, taxed “non-intoxicating” beverages containing no more than 3.2 percent alcohol. It would become a touchstone for the growing anti-temperance crowd and a springboard for the ratification of the 21st Amendment that, if passed, would forever bury federalized prohibition. Within the year, Congress began allowing states to take up the discussion of repeal and, thus, ratify the amendment. Michigan was first on April 10, 1933. Wisconsin, Rhode Island, and Wyoming soon followed. By the first of December,33 of the needed 36 states needed for repeal had voted in favor. South Carolina, on the other hand, flat out rejected any talk of legalizing liquor on December 4. It was one of only two states to do so.

This rebuff notwithstanding, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Utah each ratified the 21st Amendment the next day. With that, South Carolina was thrust into a position it had probably hoped to avoid: What position, if any, would it take in controlling its liquor?

Despite the repeal of federal prohibition, South Carolina remained steadfastly dry. Charleston, like everywhere else, appeared forever chained to a warmed-over version of the antiquated Volstead Act that continued to forbade the sale, transportation, and possession of alcoholic beverages, a situation that could be changed only by the General Assembly in Columbia. There, the fight was on. By December 14, “dry leaders” had formed an executive committee “dedicated by resolution to ‘Ultimate Prohibition,’” and appeared ready to launch an idealistic crusade to turn the state, “bone dry.” In response, Charleston and several other municipalities seemed on the precipice of revolt. The Charleston Evening Post called the state’s continuation of its prohibition law “unwise and impractical,” and The News and Courier agreed. Writer Glenn Frank stating clearly, “I have no apologies for the sins of the prohibition era. God knows they were gross enough. Dishonesty, evasion, lawlessness, and invisible government by gangsters were among the poison fruits of this futile law.”

Charleston Mayor Burnet R. Maybank, though certainly listening to his thirsty local constituents and urging them publicly to “not consider…to make any gesture of defiance,” repeated his call for the local option, a move that lawmakers could take to enable residents on the local level to vote for themselves whether or not their town could (or should) continue its prohibition.

Finally, after nearly two and a half years of both diligent debate and ridiculous rhetoric, the South Carolina House and Senate agreed on May 9, 1935 to pass the Alcoholic Beverage Control Law allowing cities and towns the right to sell alcohol and regulate its taxes, expenditures and revenue to and from licensed “free conference” liquor stores. Dealing with individual store owners this time around, according to one senator, would be far better than rehashing the old sate-run dispensary system since individually licensed stores for the “package sale of liquor,” could be more “perfectly policed [and] operate in the interest of temperance,” not to mention the more strictly controlled taxation of them would “bring in two to three times as much revenue.”

Receiving the bill, Governor Olin D. Johnson, an opponent of all forms of alcohol since taking office, could not stand up to the state’s wet majority. “I personally deplore this,” he said hours before signing South Carolina’s “Liquor Act” on May 15, 1935. “For several months efforts have been made to discover an ideal liquor bill. It is my candid opinion that no such piece of legislation has ever been written in South Carolina and I doubt very seriously if one shall ever be produced….Nevertheless, citing the majority, I am affixing my signature to the bill which legalizes alcoholic beverages in South Carolina.”

Charleston celebrated, then went to work. Maybank announced a mere $25 liquor licensing fee for Charleston retailers. Application processes for wholesale and retail dealers was organized and licenses distributed. At the same time, booze-laden trucks “rumbling into the state immediately to end a drought of legalized liquor that set in fifteen years ago” were spotted on King Street.

At precisely noon on May 27, 1935, Charleston coroner John P. Deveraux, Jr. strolled into J.F. Seignious’s newly licensed liquor store at 137 President Street. It was the very first one open in Charleston, and Deveraux was its very first customer. It had been stocked that morning with “a total of 100 cases of whiskeys and gins” all “displayed on the shelves of the store – which formerly was a garage.”

Laying down $1.75, Deveraux, for the first time in decades, legally purchased a quart bottle of Old Quaker, yet didn’t drink a drop. Instead, he delivered it to The Charleston Museum for, as the newspaper said, “posterity.” It’s still here, unopened, of course.

-Grahame Long, Senior Curator, December 2019