Bringing Them Back to Life: The Mesozoic

Bringing Them Back to Life is a blog series from The Charleston Museum that provides updates and plans for our Natural History Gallery renovations.

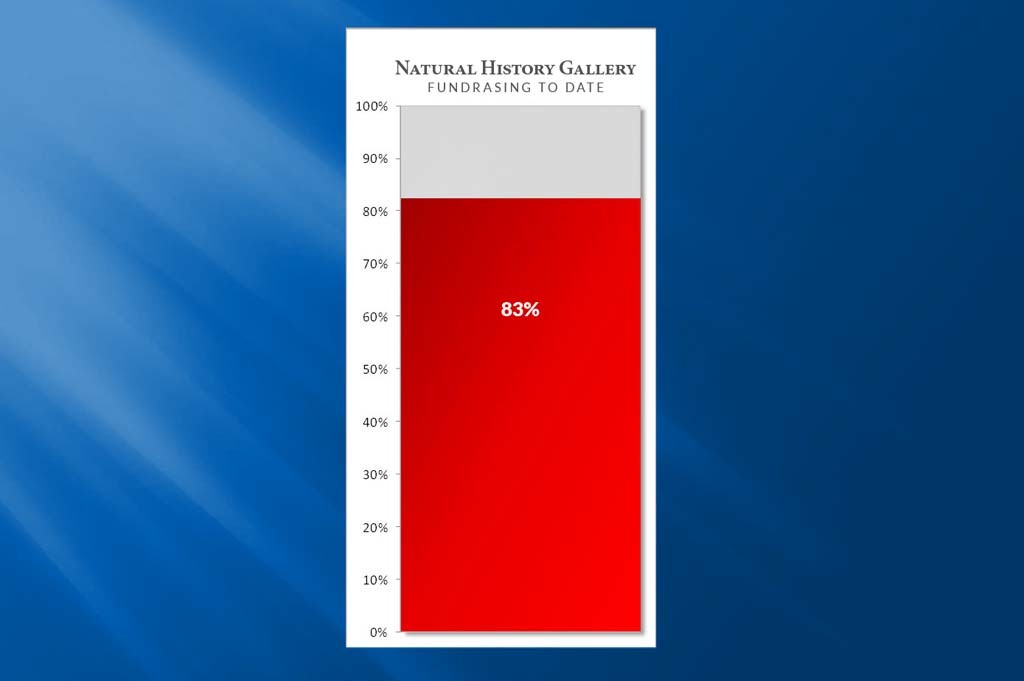

Planning, design and fundraising for the Museum’s new Natural History Gallery are proceeding nicely, and we continue to be on track for a September 2017 opening. Our current project budget is $887,000. While this may fluctuate based on the final design, which we hope to complete by this coming September, we have currently reached 83% of this goal in terms of fundraising.

We are grateful to both the Post and Courier Foundation and the Mills Bee Lane Memorial Foundation for making $100,000 commitments to the renovation. These are wonderful gifts to the project from two organizations that have made substantive contributions to our community, in general. We also recently received a $50,000 donation from a very generous individual donor who wishes to remain anonymous. Despite these successes, we still need your help, however, to reach 100% of our project goal. If you would like to make a donation to the project, please see our website, or checks can be mailed to the Museum at 360 Meeting Street, Charleston, SC 29403, attention “Natural History Gallery Project.”

In the meantime, please enjoy the following from Natural History Curator Matt Gibson on the Mesozoic Era, commonly known as the Age of Dinosaurs. This epoch will be a major component of the new gallery:

The Mesozoic

Thescelosaur

Thescelosaur

The Mesozoic Era, which began 248 million years ago, is often referred to as the Age of Dinosaurs. Although fossils from this era are scarce in the Lowcountry, there are still quite a few examples in The Charleston Museum collections. The most impressive specimens come from the end of the Cretaceous period, which began 144 million years ago (mya) and ended with the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs 65 mya. This time period will be the primary focus of the Mesozoic section of the new Natural History Gallery.

Mosasaur teeth

During the Cretaceous Period, the ocean would have completely submerged the Lowcountry. While dinosaurs were roaming the terrestrial regions in the western part of the state (i.e. Columbia and beyond), large oceanic reptiles prowled the seas that then covered the Lowcountry. The most fearsome of these creatures were the mosasaurs. Mosasaurs, carnivorous marine lizards, were apex predators that fed on any organism they could catch. They had several hunting adaptations that added to their ferocity. The lower jaw of a mosasaur could widen like a snake’s which allowed them to hunt large prey. In the roof of their mouths, mosasaurs possessed a second set of teeth (palatine teeth) that would have given them extra grip for holding on to flailing prey. Finally, there was their sheer size. Tylosaurus, which is one of the specific genera of mosasaurs that lived in the Lowcountry, could reach lengths of 15 meters (almost 45 feet)! Mosasaur bite marks have been found on fossils of ammonites, other marine reptiles like plesiosaurs, and even other mosasaurs.

Plesiosaurs are another group of marine reptiles, and potentially more well known by the general public. Plesiosaurs are identified by their thick, barrel-like bodies equipped with paddle limbs, short tails, and incredibly long necks. In popular culture, people know plesiosaurs from the legends of the Loch Ness Monster. Some have contended that the “monster” in the loch is, in fact, a plesiosaur. However, all images presented as evidence for the existence of the Loch Ness Monster have been found to have been falsified. Evidence shows that plesiosaurs went extinct along with mosasaurs and dinosaurs approximately 65 mya.

Ornithomimosaur claw w/articulated toe bones

Although terrestrial dinosaurs were not in the Lowcountry during this time period, dinosaur fossils have been found in the western half of the state, particularly around Columbia. Many of these dinosaurs would have lived near rivers or marshes. An example would be the hadrosaurs, or duck-billed dinosaurs. One of the more well represented groups from the area, hadrosaurs were herbivorous dinosaurs that would have fed on soft river and swamp plants. The fossils recovered for the dinosaurs and aquatic reptiles are all isolated elements, rather than complete skeletons. Since hadrosaurs would have either lived in or near the ocean, when they died their skeletons were scattered by the currents. Much of what we know about these animals has been learned from comparing these isolated bones to complete skeletons collected elsewhere.

At the end of the Mesozoic, all dinosaurs, mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, and a plethora of other organisms went extinct. Many scientists hypothesize that an impact from a meteorite was likely a key component of their demise. Once the Natural History Gallery renovation is complete, the isolated bones of these ancient reptiles will be on display along with several small meteorites.